Apple: “Curate No Evil.” Or How the AI Commentariat Missed the Plot (Again) And Apple Might Miss the Moment (Again).

Every tech leap sparks fear—but when platforms respond with curation over trust, the result is control, not safety. As Apple courts AI it must choose: be the Safari for AI, or the AOL. The future won’t belong to those who try to “tame” but those who let it breathe. “Curated Safety” is not an option.

Section 1: The Missing Thread in the Fabric

Ben Thompson doesn't miss much. Which is why, when he does, it's worth paying attention. His latest Stratechery analysis—ambitious in scope, confident in its framing—offers a sprawling reevaluation of AI's tectonic impact across the Big Five: Apple, Google, Meta, Microsoft, Amazon. Infrastructure, models, partners, data, distribution—it's all there, cleanly packaged in a familiar Stratechery matrix.

And yet, for all its comprehensiveness, the piece carries a hollow resonance. A sense that something vital has been left just outside the frame. Perplexity—arguably the most important interface-layer innovation in the AI space this year—is not just under-analysed. It isn't mentioned at all.

That's not an oversight. It's a tell.

When an analyst of Thompson's calibre fails to register what's arguably the first major consumer-facing demonstration of how LLMs might become infrastructure—not product—you realise that even the smartest commentariat is still wearing last season's epistemic wardrobe.

The omission is instructive, not because Perplexity is so dazzlingly advanced (it isn't, it’s dazzlingly fast and efficient), but because it reveals how deeply entrenched the framing of "AI strategy" remains in the ontology of models, tokens, and compute.

Ben Thompson in 2025 “Checks In” on his BIg Five (minus Perplexity) from 2023

The Stratechery piece takes us on a tour of giants lumbering through the AI jungle, each carrying some combination of silicon, syntax, and scale. But it never pauses to notice the narrow trail being carved by a sleeker creature entirely—one that isn't building a bigger model or faster GPU, but an entirely new way to move through the terrain.

"That trail is interface-first. Architecture-led. User-driven."

Perplexity's significance isn't that it outperforms GPT-4, Claude, or Gemini on academic benchmarks. It doesn't need to. Its genius lies elsewhere: in exposing the very irrelevance of model supremacy to most real-world users.

“To paraphrase McLuhan: the medium is no longer the message. The interface is the intelligence.”

Ben Thompson's recent return to the "AI and the Big Five" thread lands, as ever, with poise and precision. It's a welcome reevaluation of the current LLM landscape, pulling together model performance, corporate positioning, and the increasingly entangled relationships between Big Tech and Big Intelligence. But while the analysis is sharp, it feels as if it's standing on a vantage point from six months ago— just high enough to miss what's now shifting beneath the surface.

"Because something fundamental has shifted."

The conversation is no longer just about models. It's not about which company owns which layer of the stack, or how neatly an LLM integrates with a productivity suite. The axis has rotated. The friction—and therefore the value—now lies in interface, in delivery, in the grammar of interaction. The younger cohort—those under 30, the ones shaping this future more by habit than headline—don't want to "talk to a chatbot." They want access to clarity, curation, and context, on their terms. Not OpenAI's. Not Apple's. Not Anthropic's. And increasingly, not even Google's.

"They want permeability, not loyalty. And they're finding it in

Perplexity."

What Perplexity quietly represents is not just an information tool or clever wrapper—it's an early signal that aggregator logic is about to become the new UX paradigm for AI. A place where the best of multiple models are fused into one coherent response stream, where memory, history, and fluid preference are shaping how intelligence is experienced. It is, to stretch the metaphor, the electricity grid—not the power plant. And like electricity, users don't care who generates the volts. They care about reliability, clarity, and control.

The irony is that while Apple—and others—talk about user safety and privacy as their core differentiators, the net effect is a tightening of the noose on freedom of informational access. Not freedom from surveillance (a different battle), but freedom to explore, to provoke, to inquire without constraint or ideological filtering. And that, increasingly, is where the deeper tension lies.

This is the silent trailer for a longer-form follow-up I'll be publishing shortly—something I'll be try reaching out to Ben about directly. Because this is a conversation worth deepening. The AI race may not go to the fastest model, or the biggest cloud budget—but to whoever understands that the future is not in the stack. It's in the switch.

In missing this, Thompson falls into a very familiar trap. The same one that once ensnared telcos, cable providers, and software vendors who couldn't imagine a world in which users would care more about how they accessed something than what it technically was.

It's a quiet irony. For all the earnest talk of disruption and superintelligence, this moment in AI doesn't yet belong to the companies building God-like models. It belongs to the ones figuring out how humans want to interact with intelligence—on their terms, in their contexts, with their own curiosity as compass.

Perplexity doesn't appear in the matrix because it doesn't fit the rubric. It's not a model vendor. It doesn't own foundational compute. It's not lobbying to be the next ChatGPT or Claude. But what it does own is something more powerful than tokens: it owns a user habit. A new modality. A real-time semantic router for the post-search age.

That's the point missed. And it's a meaningful one—because in this moment, being clever about models isn't the same as being early on paradigms. And Thompson, for all his brilliance, has just documented the former while ghosting the latter.

In doing so, he's given us the perfect departure point. Not to critique—Ben doesn't need defending—but to explore what it means to track a revolution not just by its weapons, but by its rituals. Not just by its players, but by its protocols.

That exploration begins by naming what Perplexity actually is (in accordance with my previous articles on why Apple should buy Perplexity): not a wrapper, not a UI, not a search engine with flair. But the early sketch of something far more subversive.

It's a portal and a preference and a premonition, and the fact that the brightest minds didn't spot it is exactly the story.

2. The Interface Shift That Changes Everything

We don't talk enough about interface. Not really. We talk about UI, about friction, about onboarding flows and modal interactions, but not interface as epistemology—the thing that governs how knowledge is sought, filtered, retrieved, and, crucially, understood. And yet it's interface that shapes cognition. It always has.

The personal computer gave us files and folders, which in turn made our minds behave like file clerks—storing, sorting, retrieving. The internet gave us search bars and hyperlinks, teaching us that truth was a function of proximity: the more links you could follow, the closer you might come to some semblance of understanding. Then came the smartphone and the app, and the interface atomised again—task-centric, context-fragmented, gesture-driven.

And now: LLMs. But not as a technical marvel. As a pivot in interface logic. A new kind of cognitive prosthetic. One not built around answers, but around questions. One that listens, adapts, infers, and reshapes its own scaffolding depending on how you choose to engage it.

Except most of the commentariat—brilliant as they are—a re stilllooking at LLMs as endpoints. Outputs. "Chatbots." Or worse, "model performance." As though raw intelligence, even when compressed into trillions of weights, can be meaningfully evaluated outside of the interface that contains and delivers it.

Ben Thompson's piece, for all its strategic reach and evident depth, makes precisely this mistake. It evaluates the AI arms race almost entirely in terms of infra, model fidelity, and platform leverage—important, yes. But secondary to the revolution actually underway: the re-authoring of how we interact with intelligence itself.

Because what Perplexity represents—what it embodies—is not a"wrapper" or a fancier front-end for OpenAI. It's a rupture. A usability-level reframe of what "using AI" even means.

- Not "talking to a chatbot."

- Not "prompt engineering."

- Not "waiting to be impressed."

Instead: a search-native, citation-grounded, query-expanding, multi-modal dialogue engine that lets the user operate like an epistemic agent. Not a passive consumer of clever sentences, but a sovereign navigator of knowledge flows.

"That's the shift. Not a model. Not a chip. Not a price point. But a

paradigm."

It may look subtle. It may be easy to underestimate—especially if your benchmarks are still being scored on LMSYS leaderboards or Hacker News latency metrics. But this interface shift is no less profound than the one that took us from command lines to GUIs. From dial-up to always-on. From maps to GPS.

In Perplexity, Gen Z doesn't see a chatbot. They see an exoskeleton. A trustable, fluid, no-nonsense lens for parsing the chaos of the web, and increasingly, the world. Its design is not trying to be "magical." It's trying to be useful. Clean. Explainable. Fast. Transparent. With no puffery, no drama, and no delay. Because they're not here to marvel. They're here to find out. And then move on.

And because they don't care whether that knowledge is coming from GPT-4, Claude Opus, or Mistral. To them, the model is plumbing. The interface is the product.

Which means the conversation isn't "who has the best LLM." It's "who gives me the best way to use one."

And that's the question most strategic analysis hasn't caught up to yet. Because the mental model hasn't updated. Because for all the excitement around agents and assistants and multi-modal pipelines, most people still think they're watching a competition between smarter brains.

They're not.

- They're watching the birth of a new literacy.

- A new grammar of interaction.

- A new interface layer for intelligence.

And the first company to fully understand this won't need to win the

benchmark wars. I hey'll already be running the operating system

everyone else ends up copying.

3. Ghosts of the Garden

There's a certain comfort in gated gardens. A clean layout. Curated content. Containment disguised as care. But history has a particular sense of humour when it comes to control—it tends to loop.

Long before Apple's eWorld was quietly euthanised in 1996, the instinct to sanitise the digital unknown was already well established. The 1980s had given us PeopleLink and CompuServe: dial-up silos of communication wrapped in the illusion of breadth. You could log in, explore forums, send messages, read curated articles—but always within the confines of a platform whose walls were implied, not shown.

AOL followed the same formula and made a fortune on it. Somehow, they even bought Time Magazine (promptly destroying it) with a little more of a nod do a GUI. A content mall. A visual leash. The World Wide Web wasn't just a threat to these models—it was their unmaking. Because it didn't ask permission. It didn't curate. It routed around control.

Apple, for all its genius, has always been tempted by the symmetry of walls. eWorld was one of its early stumbles into the pre-fab utopia: a pastel suburb of safe content, shaped for middle-class nervous systems. The idea was noble enough—ease the user into this chaotic internet with pastel icons and a Newsstand metaphor. But the execution betrayed a deeper fear: that real access, uncurated access, might be too overwhelming, too impure. It flopped, of course. People didn't want eWorld. They wanted the world.

But Apple never entirely let go of the dream. You can see its echoes in Siri's arc—a voice assistant with enormous potential, slowly declawed in the name of safety and precision. Stripped of risk. Muted, lest she say something awkward. The very thing that might have made her brilliant—her unpredictability, her spark—became the reason for her anaemia. Users stopped expecting insight from her and started using her as a glorified kitchen timer. And when the product's purpose narrows to setting alarms and mishearing song titles, you know something beautiful has been buried beneath layers of risk mitigation and corporate overparenting.

This is not an Apple-specific pathology. It's a recurring cultural tic: the belief that safety and sanitation go hand in hand, that intelligence must be filtered before it's fit for public consumption. But every time we've tried to turn the world into a white box showroom—whether architectural, informational, or ideological—we've ended up somewhere sterile. Or worse, authoritarian.

Ray Bradbury saw it coming. Fahrenheit 451 was never just about book burning. It was about the weaponisation of comfort. The idea that people needed to be protected from complexity. That exposure to raw thought—unpolished, confrontational, uncurated—was a threat to their wellbeing. So they burned the books to preserve the peace. Bradbury didn't invent this dynamic. He just gave it a dystopian sheen.

The Nazis, of course, did it with less subtlety. Their 1933 book burnings were about purifying culture, stripping it of degenerate elements. But the instinct is the same: to curate minds by controlling inputs. To confuse order with truth. And to fear, above all, the open system—the one that can't be centrally policed or made "safe" for polite society.

"The parallels are not moral equivalencies---but they are structural

echoes of control dressed as care and in the name of protecting people

from themselves."

That's why this moment matters. Because AI is now entering its internet phase—the phase where the instinct will be to box it in, wrap it in parental controls, and sell it as pre-washed cognition. A safe assistant. A helpful guide. An LLM with no sharp corners. But the user doesn't want a white carpet. They want a real room.

And yes, sometimes that means red wine gets spilled.

What Perplexity understands—and what makes its omission fromThompson's piece so jarring—is that interface is ideology. A system that routes your query through multiple models, logs your path, and lets you choose how deep or broad to go is not just a feature set. It's a philosophy. It says: we trust you to decide what you want. We'll give you tools, not just answers. We'll be your compass, not your chaperone.

The irony here is thick. Apple, a company whose original Macintosh ad was a battle cry against Orwellian conformity, now risks becoming the thing it once warned against. Not through malice or neglect, but through the same old impulse: to protect the user from the messiness of unmediated intelligence.

And in doing so, it forgets the lesson eWorld taught it three decades ago:

"That you can't own the map and the territory. That freedom, once glimpsed, doesn't go quietly back into the box."

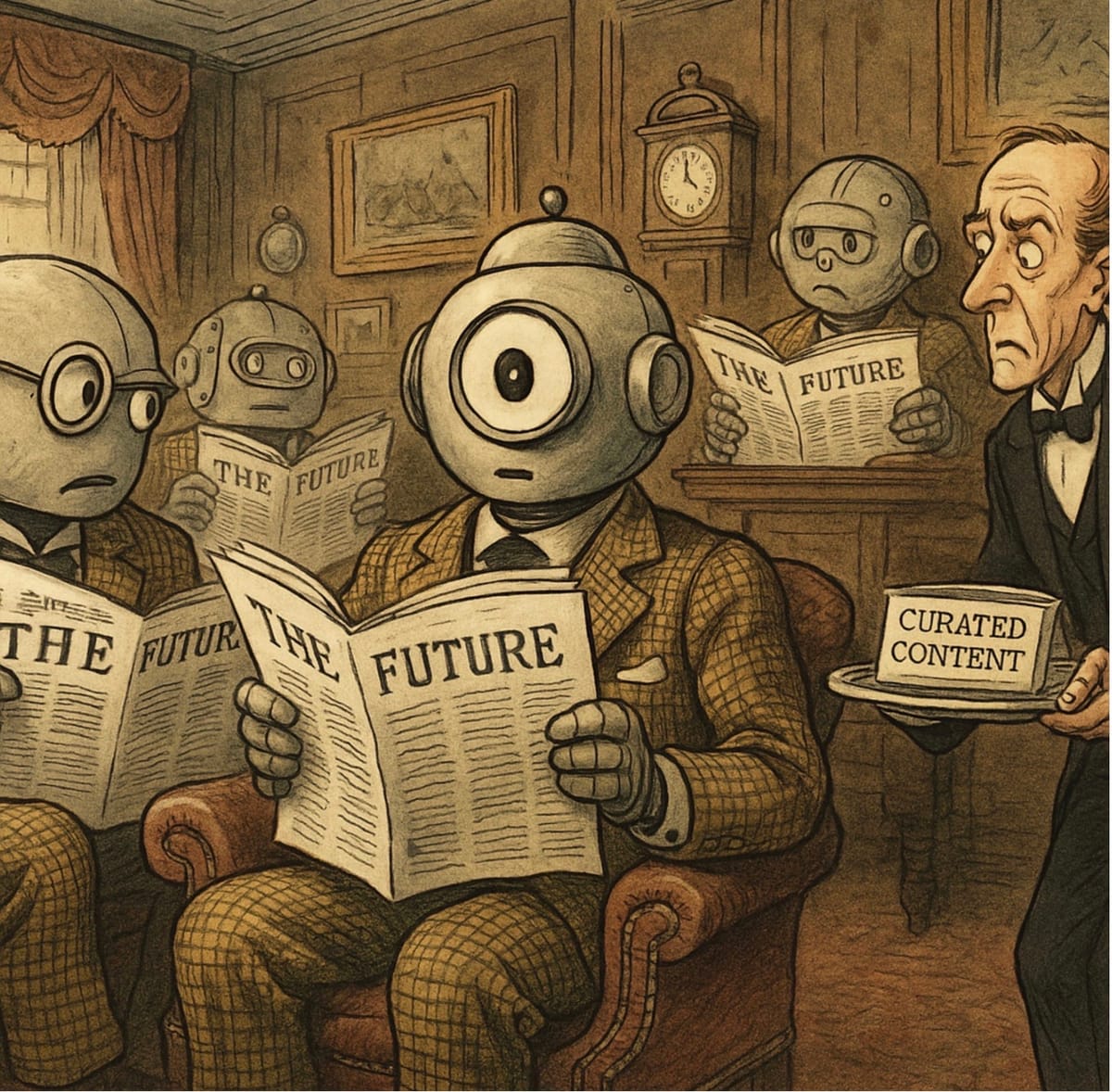

4. Perplexity as Philosophical Contrarian

Perplexity is not just another interface built atop a stack of APIs. It is a provocation dressed in a polite UI—a deliberate act of design that reframes what it means to "use AI" in 2025. For those still trapped in the binary of LLM versus search, chat versus query, it slips past unnoticed. But for anyone watching the underlying grammar of interaction evolve, Perplexity is quietly becoming something far more disruptive than a chatbot or a search engine. It is becoming the preferred interface for cognitive agency in a world awash with models.

This is not because Perplexity necessarily has the best answers. Nor is it because it outperforms Claude or GPT-4 or Gemini in raw benchmark terms—it doesn't need to. The point is not the model, but the architecture of choice. Perplexity's Labs feature, recently introduced, marks a small but important hinge point. It allows users to create persistent workspaces, store queries, return to chains of thought, and treat the system as a kind of knowledge forge rather than a glorified autocomplete. The results are not perfect, but the direction is unmistakable. It is a bet not on AI as oracle, but on AI as infrastructure—a conduit for how the user wants to think.

This distinction matters because it surfaces a fundamental truth that so much of the LLM commentary still misses: most people don't want to talk to a personality. They want to get something done. They don't want a digital assistant that pretends to be their friend. They want a fast, accurate, defensible way to answer a complex question or generate a usable draft. Perplexity is not interested in pretending to be sentient. It wants to be useful—and it is, precisely because it lets you choose which brain to borrow, routes your question to the right tool, and shows its working along the way.

In this sense, Perplexity is acting more like a router than a model. It doesn't compete with OpenAI, it uses OpenAI. It doesn't claim to be the source of intelligence, it curates access to it - and all other models. It is closer in spirit to a browser than to a bot—and that's not an accident. In fact, it is arguably the first credible example of what a browser for intelligence might look like. If Safari was built to navigate the open web, Perplexity is being built to navigate the open mindscape of large language models. It is structured not as a destination, but as a method. Not a mall, but a map. So you can find where you want to go, no matter how obscure, not be told where you can‘t go.

This is why it resonates so deeply with younger users, especially those under thirty, who are no longer awed by AI but already fluent in its affordances. For them, Perplexity is not a novelty. It is a utility. It is the shortest path to a long answer. It is Google for people who no longer trust Google to give them what they want. It is a writing companion for those who don't want a companion at all—just a fast,

well-lit tunnel to the other side of a thought.

And yet, because it doesn't market itself as a breakthrough or a revolution—because it doesn't wear its ambition on its sleeve—commentators like Thompson miss it. They remain fixated on model benchmarks and leadership battles, mistaking the map for the terrain. They see Perplexity as a wrapper, a slick UI, a derivative product. What they don't see is that it's reconfiguring the mental scaffolding of how people interact with knowledge systems entirely. That's not wrapper logic. That's interface supremacy.

In a moment where every major AI player is trying to own the core model, Perplexity is quietly building something far more powerful: ownership of the mental frame. The model may answer, but Perplexity shapes the question. And in an era where asking the right question is already 80% of the value, that makes it not a follower, but a lead indicator of where this entire ecosystem is going.

"It is, in short, not a competitor to OpenAI. It is a rebuke to the

idea that OpenAI, or anyone else, should be the only way to think with

machines."

5. Apple's Dilemma

Apple's legacy has always been framed around control—not as tyranny,but as design philosophy. It controls the hardware to guarantee performance. It controls the operating system to guarantee stability. It controls the ecosystem to guarantee experience. That philosophy built the most valuable company on earth. But in the age of large language models, that very instinct may be the thing that unravels its

relevance---not through failure, but through obsolescence.

The problem is not technical. Apple can build infrastructure. It already has. The issue is philosophical. The company that once taught the world to "Think Different" now appears reluctant to let its users do exactly that—with AI. In a landscape where users are learning to route between models, stitch their own workflows, and engage with intelligence as a modular toolset, Apple seems committed to building a curated garden instead of a functional one. Not a field of options, but a gallery of safe exhibits. The walled garden persists—not to protect the user, but to preserve the illusion of control.

Take Apple Intelligence. Much has been made of its partnership with OpenAI, and the promise that Apple will allow users to "route" their queries to external models with privacy protections intact. But beneath the hood, the architecture reveals something else entirely: a desire to ensure that the only intelligence which runs natively on-device is the intelligence Apple builds itself, or at best, tightly pre-approved. The routing is not a gesture of openness. It is a contingency plan—an

admission that Apple's own models are not yet sufficient.

There is a deeper problem, though, one rooted not in capacity but in culture. Apple's definition of privacy increasingly functions as a proxy for control. The line between "private" and "sanitised" has grown so thin that it risks dissolving altogether. The instinct to protect is becoming indistinguishable from the impulse to paternalise. And the most dangerous thing about paternalism is that it always begins as virtue.

Who wouldn't want to be protected from harmful content, from offensive speech, from unsafe queries? Who wouldn't want a world in which Siri only gives you the "right" answer? “Save Us From Ourselves,” the snowflakes shriek.

But protection, once institutionalised, always ossifies into censorship. And Apple, in trying to make AI "safe," risks turning Siri into the digital equivalent of a glass museum exhibit—technically impressive, thoroughly inoffensive, and utterly useless in the real world. It is the same instinct that muted Siri's capabilities after its acquisition over a decade ago, suffocating its potential under the weight of corporate risk-aversion and PR defensiveness. Apple didn't want a curious

assistant. It wanted a quiet one that wouldn’t rock the boat. Try asking Siri for a local abortion clinic. It won’t oblige any more. Try asking it for a plump Brazilian from an escort agency. It won’t any more. Funnily enough though, it used to. It would even tell you which one was the closest and had the best Yelp reviews (I know, because I asked a friend, obviously).

What makes this all the more troubling is that Apple knows better. Its own web browser, Safari, is a textbook example of how to build a secure, private interface without infantilising the user. It offers guardrails without cages, protection without prescription. No one would tolerate a browser that refused to visit certain sites because the company deemed them "inappropriate." And yet that is precisely the logic being smuggled into the AI domain under the pretext of safety and privacy.

The dilemma is clear. Apple can be the Safari of AI—a n elegant,performant vessel through which users explore the full topography of intelligence models on their own terms. Or it can become the AOL of AI— walled garden with beautifully pruned hedges, perfectly manicured limitations, and a slow death by irrelevance.

The former invites curiosity. The latter demands compliance.

What's at stake here is not market share. It's moral authority. Because in a world increasingly defined by information access and cognitive autonomy, the architecture of choice becomes the architecture of power.

And Apple—if it continues down the path of pre-chewed, pre-cleansed, pre-approved intelligence—risks becoming an agent not of liberation, but of limitation.

"It is not a technical mistake. It is a philosophical one. And in the

long arc of computing history, those are the ones that matter most."

6. The Ethical Frame

At the heart of Apple's current AI posture lies a question not of capability, but of consent. Not the explicit, checkbox-clicking kind we're all familiar with, but the deeper, more structural kind—the kind that governs who gets to decide what we are allowed to see, say, or seek.

It begins, as it always does, with good intentions. Apple has long marketed privacy as a virtue, and rightly so. In a digital landscape littered with predatory data practices, surveillance capitalism, and algorithmic exploitation, its stance has earned trust. But there is a fine line between safeguarding privacy and sanitising thought. Between protecting the user's data and curating the user's mind.

The irony is that this isn't new. We've seen this dance before.

Apple's own eWorld—a short-lived attempt to create a safe, Apple-branded version of the internet failed. Spectacularly. Users didn't want a theme park version of the web. They wanted the web itself—messy, vast, unpredictable. The real thing. eWorld was shuttered within two years.

AOL, Compuserve, and PeopleLink—each, in their own era, attempted to build a garden around the growing jungle of online interaction. These platforms were not built to limit access maliciously. They were designed to make the chaos legible. But

legibility came at a cost: sterility. Users quickly moved beyond the walled gardens and embraced the open web, not despite its unruliness, but because of it.

The parallels to today's AI landscape are unmistakable. Efforts to make AI "safe" increasingly echo those early attempts to make the internet tidy. There is talk of content moderation, of "guardrails," of alignment. But too often, these terms serve as euphemisms—not for safety, but for control.

And as history shows, the attempt to pre-chew information for the public almost always ends in irrelevance—or worse.

The more chilling analogues come from darker chapters of history, when totalitarian regimes ruled. These days we’re obey corporate elites.

A prompt rejected. A query refused. A topic flagged. Slowly, and often invisibly, the boundaries of thought are narrowed—not by law, but by design. Not by decree, but by default settings. And when those defaults are hidden behind the language of

safety, it becomes almost impossible to resist them without appearing reckless or irresponsible.

But safety, when imposed indiscriminately, becomes infantilisation. Adults are not children. They do not need rubber-tipped scissors on every tool they use. The notion that an adult user cannot be trusted with controversial or complex information unless it has been pre-filtered by Apple's taste-makers is not just arrogant—it is antithetical to the very spirit of intelligence, artificial or otherwise.

A robust AI interface should empower exploration, not constrain it. It should offer the user the tools to decide, not the fences to obey. Apple's insistence on owning the full vertical stack—hardware, software, model, and experience—is understandable in a product world. But in a knowledge world, that instinct becomes an echo of earlier, more restrictive architectures. And it risks turning a generation of curious users into passengers in a limousine of pre-approved thoughts with everyone else waiting in line to be processed (or more likely, just using non-Apple AI’s and “uncertified” LLMs designed to circumvent “saftety rules.” What you can programme in as safety filters after all, can always be circumvented with easy stack single-API call prompts.

Policing LLMs is doomed to failure and will only alienate the very people intended to be “protected.”

The architecture of AI access is becoming the new architecture of power. To shape what a person can ask is, in many ways, more powerful than shaping how they ask it. Apple must decide whether it wants to be a steward of exploration or a custodian of constraints. Whether it trusts its users enough to let them choose, or whether it will continue down a path where safety becomes indistinguishable from surveillance.

"Because in the end, intelligence cannot be pre-chewed. And truth,

when trimmed for comfort, dies not with a bang---but with a shrug."

7. Lessons from Past Tech Revolutions: Navigating the Cycle of Fear

If there's one thing history refuses to let us forget, it's that every leap in media or technology is shadowed by a familiar choreography: a burst of innovation, a surge of public anxiety, and the emergence of self-appointed guardians who insist the new must be tamed for the public good. The cycle is as old as the printing press and as current as today's AI safety debates— Sisyphean loop of panic, resistance, and, eventually, adaptation.

The pattern is instructive. When Gutenberg's press began churning out books, it was met with hand-wringing from scribes and clergy who feared the loss of control and the spread of heresy.

Electricity, on its arrival, was so suspect that even U.S. presidents had staff flip the switches, lest they be electrocuted.

The telephone, the radio, the television, the comic book, the video game, the internet—each in turn became the focus of moral panic, blamed for everything from the collapse of youth morality to the unraveling of social order.

The Luddites of the Industrial Revolution, smashing looms in protest, were not so different from today's critics who warn of AI's threat to jobs, privacy, and even civilisation itself.

What persists through these cycles is not just fear, but the reflex to control—often justified as a matter of public safety. Gated gardens, walled platforms, and curated content have always been the first response to the unknown. Yet history's verdict is clear: over-curation rarely survives contact with the real world. The open web outlasted AOL's pastel walled garden because users, when given the choice, preferred the mess and possibility of unfiltered access to the safety of pre-approved content.

The lesson? Fear is normal. So is the urge to contain. But the most robust systems—those that truly empower—are built not on paternalism, but on trust, transparency, and agency. Safety, when it hardens into control, breeds irrelevance. The most successful technologies have always been those that invite users to explore, adapt, and shape the tools to their own ends, not those that insist on protecting them from themselves.

AI is no different. The panic is predictable, the calls for oversight and regulation

inevitable. Butif we are to avoid repeating the mistakes of past revolutions, we must recognise that the real risk is not in letting people ask the wrong questions, but in designing systems that refuse to let them ask at all.

The challenge is not to eliminate fear, but to channel it—into pragmatic safety engineering, ethical transparency, and above all, a commitment to user empowerment over institutional control.

Because every time we have chosen containment over curiosity, the result has been the same: the garden withers, the world moves on, and the revolution finds a new, more open home.

| Historical Innovation | Initial Fear/Response | Long-term Outcome | Lesson for AI Safety |

|---|---|---|---|

| Printing Press | Loss of control, misinformation | Democratisation of knowledge | Openness and access drive progress |

| Electricity | Health, safety concerns | Ubiquitous adoption | Early fears fade with familiarity |

| Early Internet | Walled gardens, curation | Open web prevails | User agency trumps over-censorship |

| Social Media | Misinformation, privacy worries | Ongoing adaptation, regulation | Balance innovation and oversight |

| AI (Current) | Job loss, existential risk, control | TBD | Pragmatic, pluralistic safety focus |

"The cycle will repeat until we learn the real lesson: the future belongs to those who trust users with the raw material of intelligence—and who design for agency, not anxiety."

8. Closing Provocation

There is a pattern here. Not a conspiracy, not a masterplan—but a reflex. A design instinct too old to be called new, and too recent to be fully recognised for what it is. We've seen it across the epochs of computing, the architectures of interaction, the software of society.

The reflex is this: when a new medium emerges—especially one that multiplies agency—it is met with a tidy panic. And the instinct of the platform, almost without exception, is to calm that panic by making the medium safe.

But safe for whom?

Every time a paradigm shifts, there is a scramble to reassert control—not because bad actors lurk, but because entrenched actors panic. That panic takes many forms: interface lockdowns, usage constraints, safety defaults, and curation masquerading as clarity. It is a technocratic anxiety about what might happen if the user is trusted too much. And Apple, despite its design purity and rhetorical emphasis on "freedom," has a long and uneasy relationship with trust.

With Siri, Apple muted the very features that might have let it grow. The instinct to prioritise safety and polish over mess and growth turned what might have become the most powerful assistant of the decade into a compliant secretary, polite but incapable. When it came to eWorld, the attempt to tame the internet into an Apple-branded playpen fell flat because the web, like intelligence, does not take kindly to borders. And now, with LLMs at its doorstep, Apple once again risks confusing containment with control.

The spiral is tightening.

Across the industry, from Meta's algorithmic curation to OpenAI's increasingly moderated interface decisions, the urge is the same: to make intelligence platforms “respectable.” To make them palatable. To make them safe enough for a boardroom, a classroom, or a senator's iPad. And yet, intelligence—true, emergent intelligence—is not polite. It is not linear. It is not reducible to a keyword list of safety concerns or filtered prompt outputs.

Real intelligence, like real culture, is messy. It offends. It provokes. It expands in unpredictable directions, often through friction, sometimes through fire.

To claim to want intelligence while filtering out its more difficult expressions is to demand a fireplace with no smoke, or a tide with no salt.

It is aesthetic puritanism pretending to be moral clarity. And it is deeply, dangerously infantilising.

What we are seeing in the AI interface debate is not merely a product decision. It is a cultural one. And Apple, for all its rhetoric about empowering the individual, now stands at a threshold where it must decide whether it is a steward of freedom—or its curator and undertaker, creating a pretty picture out of a dead end.

Because curation, in this context, is no longer neutral. To flatten intelligence into a set of pre-approved outputs under the guise of "safety" is no less controlling than China's firewall. It is simply marketed better. The West now wears its censorship in silk gloves. Harm reduction becomes harm denial. Context is stripped in favour of compliance. And adults, who can already buy Mein Kampf or Fifty Shades of Grey or visit any number of forums or archives across the open web, are told that querying certain topics via AI is "not allowed" or “Violates content restrictions,” simply because you ask it for a picture of a child holding an iPhone running Perplexity in a sea of adults still searching Google (which is the response I received when creating images for this article).

Not because it is illegal. But because it might be uncomfortable.

That is not alignment. That is a velvet authoritarianism that trades agency for convenience and cloaks its power in parental concern. The argument that users must be protected from what they might find, or might ask, or might want to explore—when those things are already freely accessible in other formats—is not a technical limitation. It is a cultural betrayal.

Apple would do well to recall its own role in the liberation of digital agency. Safari does not censor the web. It does not pre-screen results based on moral ideology. It trusts the user to explore. Why should Siri, or Apple Intelligence, be different? If Apple is to be the hardware and interface layer for the coming age of cognitive companions, it must make a choice: build a cathedral of curated thoughts, or enable a bazaar of uncensored exploration.

Because there is no middle ground. A "semi-open" AI is not open. A sandboxed LLM with pre-cleared dialogue paths is not intelligence. It is theatre. And increasingly, the public knows the difference.

The generation now using Perplexity, embracing Labs features, mixing Claude with Gemini, layering prompts and memory tools, is not asking for politeness. It is asking for precision. For freedom. For agency. These are not children begging for boundaries. They are citizens demanding sovereignty.

Apple can either meet them there—or lose them forever.

The age of neat answers is over. We are in the era of interface pluralism, where intelligence is a fluid, plural, multi-headed phenomenon. The companies that try to lock it down, soften its edges, make it "family-friendly," will discover what every empire learns eventually: you cannot domesticate revolution.

"And AI, in its true form, is not just a product class. It is a revolution in how we interface with thought itself."

That revolution will not be won by those who build the best models. It will be won by those who let intelligence breathe. Not in a white room. Not in a safe space. But in the raw, unvarnished, gloriously human arena of curiosity, dissent, risk, and wonder. That is the battle for the future of AI.

Apple, for all its power, must decide—before it is too late—whether it wants to be the guardian of that future, or merely the gatekeeper of what it arbitrarily decides is safe to be allowed, to be imagined, and safeguard itself into irrelevance by the next generations who want utility and access.

Nobody is going to tolerate being told off for violating some obscure safety Rottweiler algorithm because they’re trying to have a conversation or do some research. Or just having some fun. That’s not Apple’s call to make. They’ll switch platforms.

“In fact, the platform could begin, to cease, to matter.”

Tim, over to you. Make your choice. Make it wisely. Apple has been here before. Remember eWorld. Remember what Apple squandered by neutering Siri. Don’t make the same mistake again. You’ve got one chance, to make the right choice. Please, get this right. Defend, not offend, freedom.

@Tommo_UK — London, Wednesday 25th June 2025

tommo-fyi.ghost.io

Author's note: This is not a rebuttal in anger. It's a continuation

in kind, of a trigger @benthompson of @stratechery triggered when I read his article. Ben, if you're reading, I'd love to include your thoughts in a

follow-up. Because the stakes here go far beyond Apple.

Please, share this newsletter with your friends, colleagues, wealth advisor or liquidator - whatever is your poison - or friendly CNBC anchor. Brian Sullivan, are you still reading?

And if you have friends at Apple, Perplexity, or any AI shop - or especially if you can ping this to @benthompson or @stratechery and get his attention send it to them too. Get a conversation going - and I don‘t mean with a chatbot.