Target Acquired: How Apple Keeps Painting the Bullseye on Its Own Back

Apple isn’t being picked on by regulators. It’s practically inviting scrutiny. In trying to protect its moat, it may be digging a reputational trench. Here’s how it got here—and what it must change.

There’s a popular myth among Apple loyalists that the company is being unfairly persecuted by global regulators—singled out for its success. But that narrative falls apart under scrutiny. The truth is more strategic and more dangerous: Apple has systematically chosen the most adversarial paths when confronted with regulatory change. Instead of leaning into its reputation for design-driven clarity, it’s leaned into defiance—turning oversight into ideological warfare, and risking fragmentation of the very ecosystem it once curated so carefully.

This isn’t just about App Store rules or WebKit restrictions anymore. With every lawsuit filed, delay tactic deployed, and commission scheme defended, Apple isn’t defending innovation. It’s defending incumbency. And it’s doing so with such theatrical resistance that regulators are no longer reacting—they’re organising. What began as technical scrutiny is fast becoming political will. And if Apple doesn’t recalibrate, it risks becoming not the gatekeeper of the ecosystem—but the reason it fractures.

Something Good: The Fortress That Worked

Apple’s Integrity Advantage

For much of the past two decades, Apple’s tight vertical control delivered not just convenience but conviction. It was the antidote to chaos: a walled garden where users didn’t get scammed, developers had a clear path to monetisation, and privacy came as standard. In a world flooded with surveillance capitalism and dark patterns, Apple felt like the principled insurgent—opinionated, opaque, and deeply user-aligned.

“Apple earned its walled garden. But walls don’t scale without gates.”

Apple’s ecosystem was a fortress—one that operated with uncanny cohesion across hardware, software, services, and design. The App Store? Safer than Android’s fragmented marketplaces. WebKit enforcement? Security, not sabotage. Apple Pay and Touch/Face ID? Frictionless, fraud-resistant innovation.

For years, this control wasn’t questioned—it was admired. In fact, many regulators tacitly supported it. The singularity of the App Store was tolerated precisely because it provided a secure, reliable consumer experience. But this tacit approval was never a blank cheque—and Apple has spent years overspending the goodwill that came with it.

In Jobs-era diplomacy, we saw balance. iTunes was negotiated carefully with labels and regulators. Apple understood how to work on the edge of regulatory frameworks without tipping into hubris. The App Store, by contrast, has seen Apple use its dominance as a blunt instrument. It no longer cultivates consensus—it imposes it. That shift hasn’t gone unnoticed.

Something Worrying: The Strategy That Became a Stance

From Stewardship to Siege

Somewhere between the triumph of Apple Silicon and the regulatory tremors of the Digital Markets Act, Apple’s philosophy calcified. The company that once used constraint as creative fuel began using it as corporate cover. Rather than adapt to emerging standards, it began to resist them by default.

“It stopped managing risk and started daring regulators to escalate.”

The European Commission. The UK’s CMA. The US DOJ. South Korea, Japan, Australia, India. There’s no longer a single continent where Apple isn’t under scrutiny—and yet, Apple’s response pattern remains chillingly consistent: minimal accommodation, maximum delay, and when pushed, aggressive litigation.

Take the DMA. Instead of offering proactive compliance, Apple delivered convoluted half-measures: alternative app marketplaces laden with caveats, complex fee structures, and opt-in consent walls that regulators immediately decried as non-compliant. In the UK, Apple’s defence of WebKit exclusivity included the now-infamous argument that browser competition would chill innovation—an assertion so out-of-step with developer sentiment it bordered on satire.

Even loyal commentators are beginning to blink. In a widely read piece, John Gruber mused—perhaps half-jokingly—that Apple might be better off ditching Europe altogether rather than submitting to a patchwork of regulatory demands. As ludicrous as that sounds, it captures the slow horror of Apple’s strategy: in trying to protect the coherence of its platform, it may accelerate its fragmentation.

And here’s where it gets dangerous: Apple’s refusal to moderate its behaviour is undermining its one legitimate moat—security. The idea that iOS apps are curated exclusively in the App Store has always been a strong argument for consumer safety. But Apple’s abuse of that exclusivity—through pricing controls, opaque guidelines, and punitive commissions—has opened the door for regulators to question the very premise.

Had Apple been less aggressive, it’s entirely plausible regulators would have left the security model intact. Instead, by insisting on absolute control of distribution, while simultaneously extracting maximum rent from developers, Apple Is inviting regulators to compromise the very integrity model it claims to be defending.

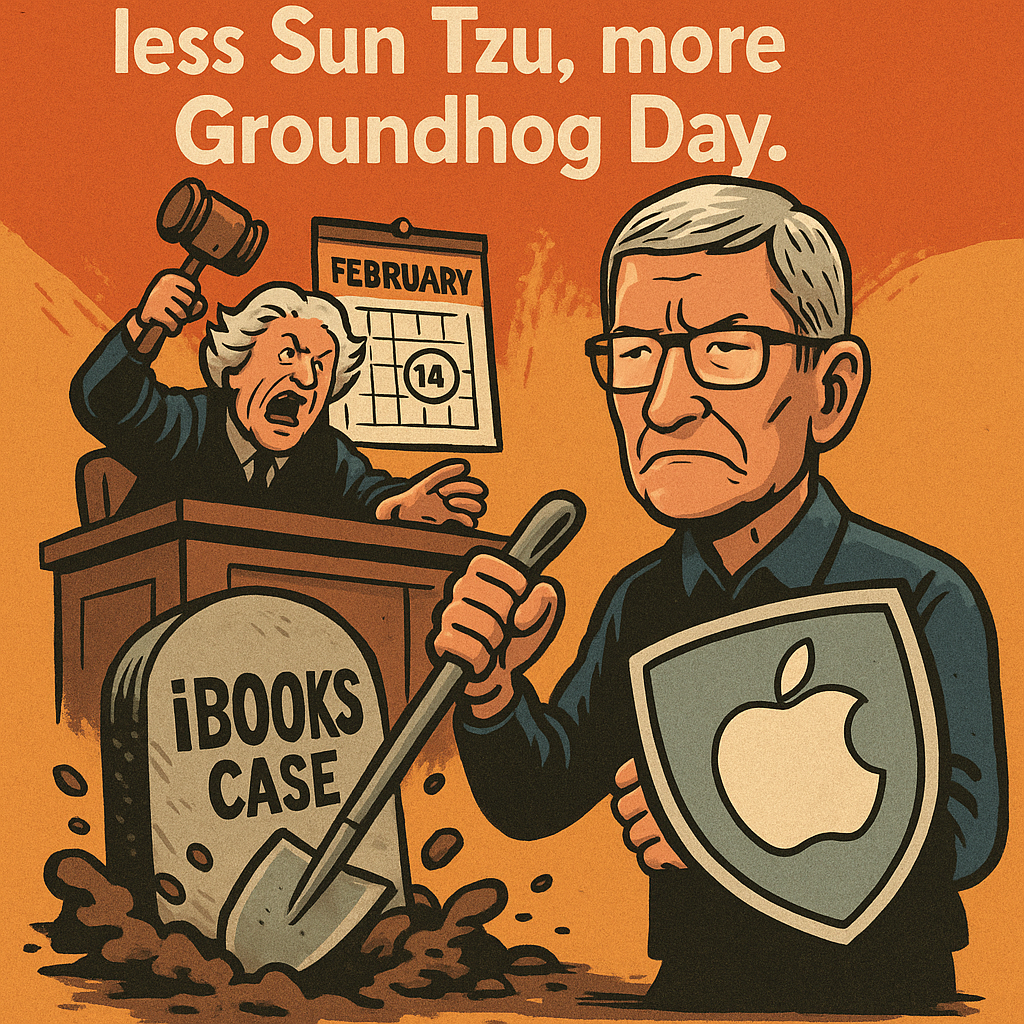

“Apple’s litigation playbook is less Sun Tzu, more Groundhog Day.”..

The iBooks fiasco should’ve been a warning shot. Instead, it became the template. Faced with legitimate regulatory challenge, Apple doesn’t negotiate—it digs in, wraps itself in stainless steel righteousness, and dares the courts to blink first. It lost the iBooks case. It’s floundering in App Store antitrust. And yet it keeps walking back into the same courtroom with the same doomed strategy and the same baffled look when the gavel comes down.

“This isn’t strategy. It’s a pathology.”

Apple has become institutionally allergic to compromise. Even when the stakes are low. Even when the optics are worse. It fights to the bitter end, not to win—but to prove it never gave an inch. A company once famous for knowing when to say “no” now seems incapable of saying “yes” to anything except another round of discovery motions.

“Apple’s reluctance to give an inch is making it the poster child for platform overreach.”

And with every courtroom clash, Apple moves closer to losing by force what it could have retained by consent.

Something Hopeful: From Opponent to Architect

How Apple Can Reset the Relationship

Apple doesn’t need to roll over. It just needs to evolve. The path forward isn’t surrender—it’s stewardship. Apple can maintain its standards and values while participating in global digital governance with foresight, not force.

“Privacy is Apple’s crown jewel. But leadership also means knowing when to bend, so the whole structure doesn’t break.”

What might this evolution look like?

- Compliance by design, not compulsion: Apple could embrace region-specific strategies that preserve user experience while honouring legal frameworks.

- Open APIs with guardrails, not silence: Rather than wait for court orders, Apple can invite regulated innovation through structured sandboxing and developer agreements.

- Shared accountability, not fortress thinking: If Apple truly believes its model is safer, it should welcome competition—and prove its superiority through user preference, not technical lock-in.

- Transparent, collaborative posture, not courtroom posturing: By co-designing with regulators, not reacting to them, Apple can influence how frameworks are shaped rather than merely comply with them post-facto.

These aren’t signs of weakness. They are signs of scale.

This is what Steve Jobs understood when he brought music labels, studios, and publishers to the table with iTunes. Apple could dictate terms because it understood the need to make everyone feel like a stakeholder—even regulators. The App Store era lost that lesson.

Conclusion: When the Target Is Self-Painted

Apple used to be the company that redefined markets through elegance and clarity. Today, it risks being remembered as the company that dug in its heels while the world changed around it.

It doesn’t need to lose its edge. But it does need to recognise that its edge is now a blade held to the throat of its own ecosystem.

“Apple thinks it’s defending its principles. But from the outside, it just looks like it’s saying no to the future.”

As governments increasingly coordinate across jurisdictions, and as developer communities grow more vocal, Apple’s days of unilateral ecosystem control are numbered. What comes next is either a carefully evolved Apple—one that still shapes the digital future—or a splintered legacy of missed moments, botched adaptations, and self-inflicted wounds.

The target isn’t Apple’s success.

The target is Apple’s refusal to lead beyond its own perimeter.