The Horizon Is the Wrong Place to Aim: Apple, AI, and the Illusion of Perfectionism Safety.

Do LLMs need to be perfect? Or just human enough to understand us—and flexible enough to grow with us. This is a question nobody is asking, and Apple has not yet addressed. Even legends like David Parnas are screaming for “safety über alles.” Roll on WWDC 2025. Will it be an Event Horizon moment?

AI, Apple and Parnas - Published: 01 June 2025 - Tommo_UK

Apple’s AI: A Legacy Problem, Not a Visionary One

There was a time when Apple didn’t follow trends—it set them. It didn’t ask where the puck was. It skated to where it was going, and then showed us how to play the game. These days, it’s hard to tell if they’re even watching the rink.

Apple’s approach to artificial intelligence—and particularly large language models (LLMs)—has been a textbook case in corporate cognitive dissonance. Obsessed with control, fearful of imperfection, and pathologically committed to getting it “just right,” Apple seems to be mistaking hesitation for caution, and minimalism for mastery

Mark Gurman’s Sunday Bloomberg Ablutions Thoughts

Coincidentally today, Mark Gurman has formed similar conclusions about the risks to Apple but for rather less cogent and poorly articulated reasons, whilst performing his Sunday ablutions in time for his weekly Bloomberg column.

Over at Bloomberg… or rather, Gurman’s pondering’s while he brushes his teeth reflecting himself in the mirror and Apple and AI, for the modest price of $299/year (or roughly $24.92/month if you want it to hurt less, or 99 cents for a digital only subscription, or something like that), has delivered this week’s breathless dispatch:

Apple, having unveiled “Apple Intelligence” with much fanfare a year ago, is now scrambling to convince anyone it still matters.

To paraphrase Gurman (because he doesn’t say very much):

• The launch last June was more “branding than breakthrough.”

• Siri’s still not ready.

• Genmoji wasn’t quite the AI moonshot Tim suggested.

• Apple’s “priority notifications” didn’t exactly reset the bar.

• And despite months of hype, Apple’s AI is largely reactive, forgettable, and late.

Gurman’s kicker? Apple’s most significant AI news at WWDC 2025 will be that it’s finally opening up its tiny ~3 billion parameter on-device models to third-party developers—models which, he notes, are still far less capable than anything OpenAI or Google are running in the cloud.

If this all sounds eerily familiar to readers of this blog, that’s because it is. If it also sounds like something I wrote six months ago over at www.ped30.com that’s because I did and discussed it at length with other commentators there.

So you could pay Bloomberg $300 a year to read that Apple’s been late, lacklustre, and quietly catching up… or you could get it here in real time, with a side of dry wit and zero hedge fund disclaimers.

As for Gurman’s final note that Apple is “in a bind” with “little to add to the conversation”? That’s true.

But what he misses is the bigger picture and question—yet again—is that Apple doesn’t just have little to add.

It may have missed the cultural moment entirely. A bit like Gurman.

Back to my history lesson and what happens when Apple puts “Safety First” and rewinding 30 years. As it has with so many public-facing services in the past, including its disastrous “safety first” curated online presence, eWorld, Apple has form on safety first, stickiness second, and causing an almighty lack of interest.

eWorld: Apple’s Dream of the 90’s, launched in 1994.

Back in 1994, Apple launched eWorld—a pastel-coloured, cartoon-laced online village that imagined the internet not as an open highway, but as a sleepy, well-groomed cul-de-sac. You didn’t “browse”; you strolled. You didn’t surf; you politely knocked on the door of the eWorld Post Office or Library and hoped someone let you in. It was charming, quaint, and thoroughly designed—an online environment where the user experience was controlled down to the metaphor. And like any good metaphor, it had its own town square, its own bulletin board, and its own cheerful little guides (think: Clippy with better manners). It was also expensive, sluggish, over-moderated, and… profoundly limited.

The dream was noble: create a safe, curated space where the internet could be civilised, beautiful, and digestible—especially for new users. But the reality felt like being trapped in a Norman Rockwell painting while everyone else discovered a neon-lit metropolis just a click away. eWorld was Apple’s gated community at a time when everyone else was discovering the interstate. And when users realised there was an off-ramp to something bigger, faster, and weirder, they floored the gas pedal and never looked back.

Fast forward to today, and you can hear the same nervous idealism echoing in Apple’s slow, buttoned-up approach to generative AI. The talk is of curation, safety, responsibility, and waiting until it’s ready. But once again, a meticulously crafted walled garden is being pitched in an era where most users are already off-road—experimenting, failing, creating, and evolving in real time. Apple’s instinct to design a safer, cleaner, more human-centred AI experience isn’t wrong.

eWorld didn’t just quietly fade away—it belly-flopped into digital oblivion by March ’96, unloved and unmissed. It turns out that building a pastel-coloured gated community for internet users, complete with cartoon signage and a 2-hour curfew, wasn’t quite the revolution Apple hoped for.

The lesson? Walled gardens might look tidy on a brochure, but people don’t move to the internet to be told where to sit. Apple, to its credit, learned to keep the internet mostly open even as its own ecosystem calcified.

Facebook, of course, missed that memo and has been busy rebuilding eWorld with surveillance bonuses. But here’s the truth: you can’t slap a velvet rope across the open web and expect people not to notice the superhighway right next door. The dream of the curated, closed internet is as dead as eWorld. What Facebook did is what Apple could have done if it hadn’t made a walled garden of itself, and Apple AI looks horribly in danger of showing the same lessons haven’t been learned.

If Apple’s approach to AI and LLMs ends up another eWorld—safe, sealed, and irrelevant—the puck won’t just have moved. It’ll be in 2027 by the time Apple finally decides to take the shot.

Moving on: 1994 to 2025, 30 years later: is history repeating?

Last year’s WWDC 2024 should have been the moment Apple entered the conversation around AI. Instead, it launched a damp squib of a vision that was half-promised, barely architected, and wholly unconvincing. Siri’s reinvention never came. The rumoured “Apple GPT” vanished into the ether. And for all the internal reshuffling of software engineering teams and talk of privacy-focused architecture, Apple missed the one thing it used to excel at: timing.

“LLMs don’t need to be perfect. They need to be human enough to understand us—and flexible enough to grow with us. That’s what Apple seem to have forgotten.”

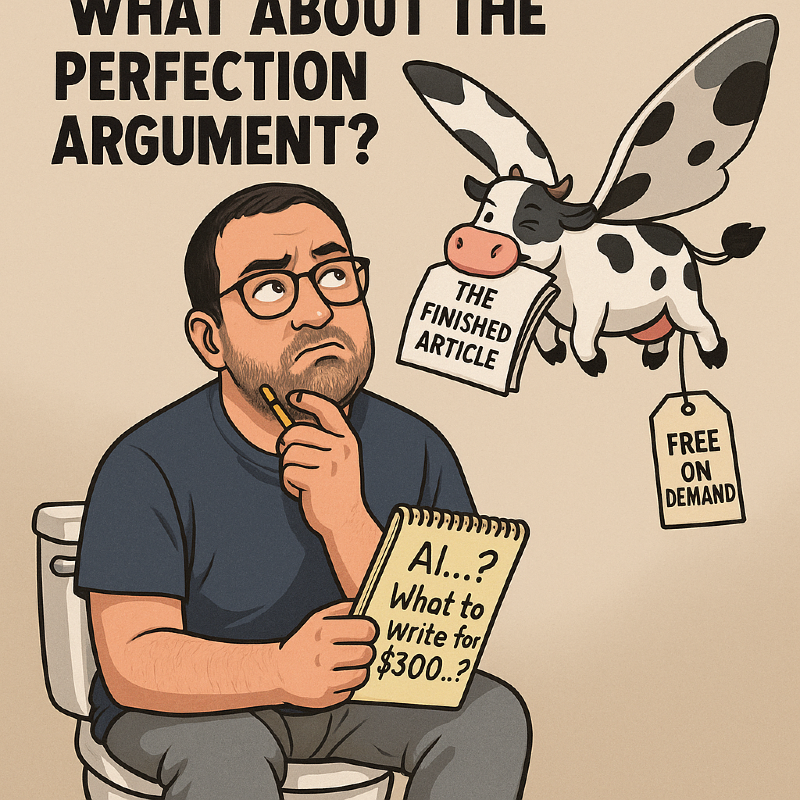

What About the Perfection Argument?

One of the more common refrains—offered earnestly by well-meaning commentators—is that Apple’s delay is strategic. That it is working quietly, behind the scenes, perfecting a product that will blow us away. That it won’t launch an LLM until it’s “ready.” That Apple always delivers in the end. Someone must have forgotten to renew the logistics agreement in the last five years, because not just has very little arrived, but very little seems to be ready to ship, if it did at all. The unspoken implication: others cut corners, Apple doesn’t.

Except that’s not really true anymore.

From Car Crash to a lack of Vision, a Siri with dementia to AI which was more artificial then intelligent: Tim’s boast, “look at Genmoji. They’re great.”

From the Apple Car debacle to the AVP’s underwhelming debut, and now to the embarrassing U-turn on their AI roadmap—Apple’s engineering reputation has taken more than a few knocks. And while Apple Silicon remains a triumph, software—where intelligence lives—has become its weakest link.

“Apple’s greatest liability in AI isn’t its hardware. It’s the illusion that the same design perfectionism that brought us the iPhone will somehow work in a field that rewards messiness, recursion, and real-time evolution.”

Why LLMs Are Built Differently

Unlike traditional software, large language models are not deterministic machines with neat rulesets and binary outcomes. They are probabilistic synthesis engines. Their power lies in ambiguity—learning through iteration, not instruction.

This is not a bug. It’s the point.

To ask an LLM to behave with the same fixed consistency of legacy software is to ask a child to never mispronounce a word or question a teacher. Intelligence—artificial or human—does not emerge from rigid compliance. It grows from recursive learning, contextual framing, feedback loops, and human-in-the-loop evolution. If you constrain it too tightly, you don’t get safety. You get sterility.

Apple, to date, has shown little sign it understands this.

Apple’s AI Paranoia: Safety or Stagnation?

Let’s grant the privacy argument. Let’s even concede that Apple is right to prioritise user trust. But here’s the problem: Apple has mistaken containment for control, and control for reliability. In AI, reliability doesn’t mean never making mistakes. It means knowing how and when to learn from them.

What other companies—OpenAI, Anthropic, Meta, Google—understand is that you can’t build truly human-centric systems without letting them evolve. Apple, in contrast, seems to be trying to curate intelligence in a lab: white coats, glass walls, and a checklist of safe topics. A bit like eWorld, 1994.

“Apple’s fear of hallucination is beginning to look like a hallucination of its own—that AI can be boxed, tamed, and shipped in a white retail box without ever touching the messy reality of human complexity.”

On the Edge: Why AI Development Lives at the Limit

AI development is an edge pursuit. Not in the marketing sense—but in the fundamental architecture of how it learns.

To push an LLM forward, you must risk it going too far. To find balance, you must let it unbalance. This is the same logic behind social interaction, emotional growth, and indeed, all creative human learning.

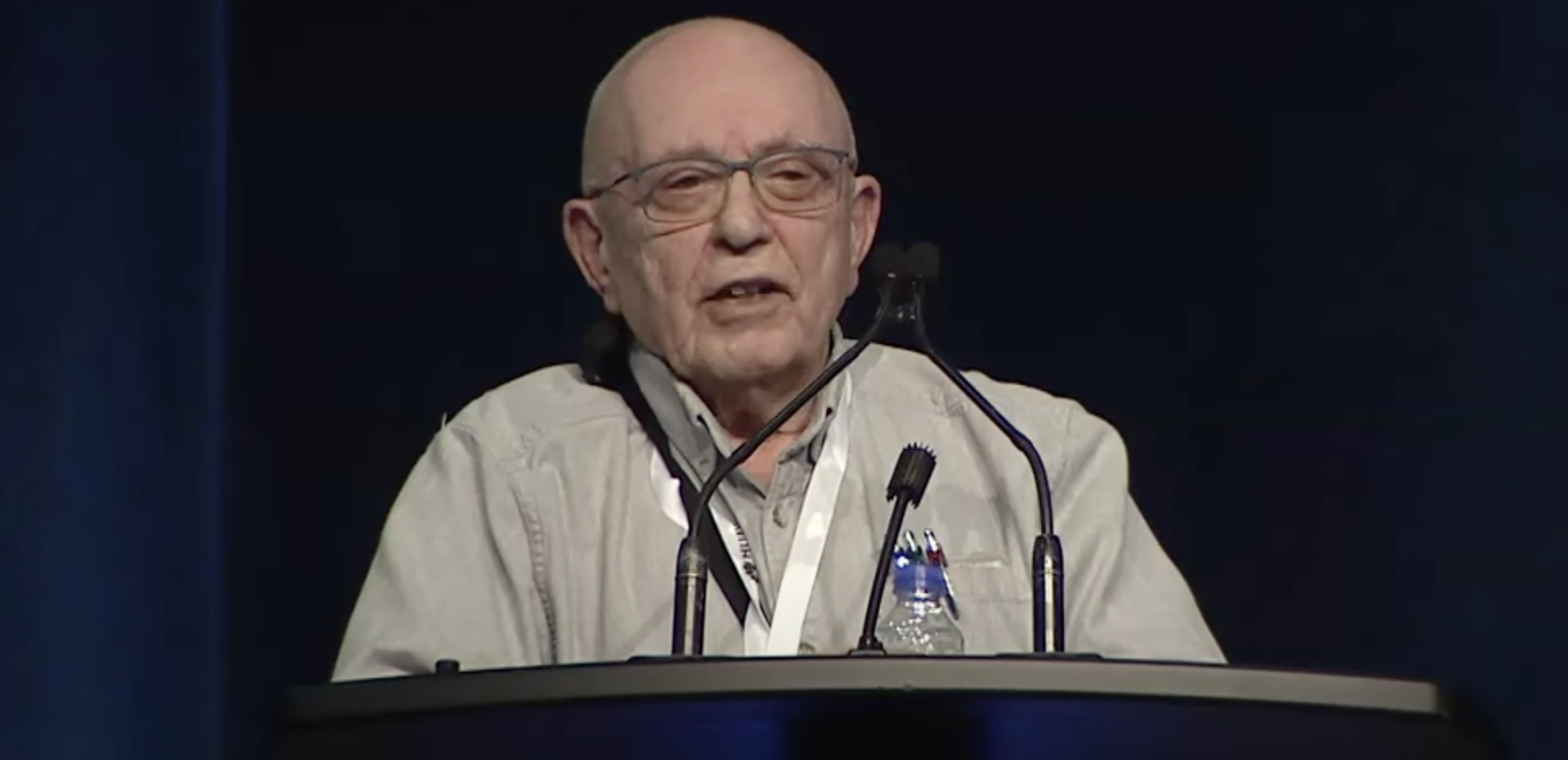

David Parnas—the legendary software engineer whose recent commentary helped restart this debate—argues for deeper safeguards, stricter oversight, and a regulatory approach to AI that treats it like traditional software. He’s not wrong about the risks. But he may be wrong about the framing.

LLMs aren’t like nuclear reactors or aircraft control systems. They are not built for zero failure operation. They are built for continual interaction with live human feedback—precisely so that they can evolve alongside the cultures, languages, and ethics of the humans who use them.

So What’s Apple’s Problem, Then?

The problem is twofold:

1. Apple fundamentally doesn’t trust emergent systems. Its entire operating model is based on closed loops, tight guardrails, and top-down control. It has always designed products, not platforms—ecosystems, not experiments.

2. Apple is no longer where the puck is going. Its competitors are releasing iteratively, learning in public, integrating LLMs into workflows, education, therapy, productivity, gaming, and research. Apple is still tinkering with what to call its LLM and dropping hints that internally they have ”an LLM” (as if that broad definition means anything) which is smaller and more efficient and can run on-edge on device.

For those not in the know, those open source models have been around for a couple of years, and Apple could have achieved this by deploying them in much the same way it adopted a UNIX-based OSX derived from NEXT-OS when OS9 had become such an internal mess that there was simply no way of launching OS10 - the codebase was unmanageable.

Back then they made the simple but hard choice, too buy in and evolve, because Apple realised they were about to start falling behind expectations at a rate which would be fatal to the company’s reputation and future. Re-enter Jobs, who threw out the old and half its product lines, and virtually rebuilt the company from scratch. He took the ultimate risk, and received the ultimate reward and accolades for it. Tim Cook was his genius COO, now the CEO, but appears to have a problem with stepping outside of his safety zone, and trusting others, with openly disastrous consequences, to make those calls for him.

“If you treat an LLM like a whiteboard, you get discovery. If you treat it like a toaster, you get settings. Apple keeps trying to make a toaster. The world already moved on and just wants to order food by delivery. Toasters are for pensioners, along with stoves.”

What About the Real-World Use Cases?

Let’s talk about what’s working.

• OpenAI’s GPT is now being integrated in real-time dialogue platforms, educational tools, and therapy-grade co-regulation engines.

• Anthropic’s Claude is powering advanced logic-heavy research workflows with minimal prompt engineering.

• Perplexity and other semi-LLM agents are driving sophisticated knowledge retrieval models in both consumer and enterprise applications.

(Let’s not mention Gemini. It’s a bit of a glorified Siri.)

These tools are not perfect. They hallucinate. They occasionally misunderstand tone. But they improve. They adapt. And most importantly, they are being used—at scale, right now, in ways most consumers and even industry experts simply cannot comprehend because they’re equating LLMs to search engines, not augmented expert assistants.

I say this as someone who has built LLM-based therapeutic agents deployed in real clinical settings. I’ve watched them outperform 80% of trained professionals—not because they are infallible, but because they are consistent, contextual, and always learning. What other technology do you know that can reflect your emotions, track breakthroughs, and grow with your inner life? I’ve seen what’s the equivalent of several years of traditional therapy succeed in a single session of working with my clients over an extended 3-hour deep dive between the two, overseen by be, achieve discovery and closure of deep trauma in some of the most stunning PTSD and trauma-induced examples of human suffering I could describe.

So who you gonna call? Not Ghostbusters

And definitely not an “intelligent” Siri, still designed to work within the walled garden, suffocating to death just like Apple’s HomeKit (later called just Home) ecosystem has because of a refusal to properly adopt and integrate open standards and utility in its implementation of home automation.

What About Public Fear?

The AI moral panic—like all tech panics before it—has found fertile ground in mainstream media. LLMs are portrayed as either soulless bots or demonic sentience. Schoolteachers ban them. Executives fear them. Parents misunderstand them even while secretly using them to help their children with their homework (the few parents, that is, still “parenting” their kids).

“But the reality is more mundane: they are useful. They are here. And they are already shaping how the next generation thinks, learns, and creates.”“The real danger isn’t runaway AI. It’s runaway fear—used by those in power to suppress innovation, maintain control, and keep the public too frightened to explore.”

The printing press, the telephone, the personal computer—each sparked moral panic. None killed us. All transformed us. LLMs will be no different.

What About Developers?

For independent developers and startups, the idea of building inside Apple’s eventual AI walled garden is borderline terrifying. Ask anyone who’s seen APIs restricted mid-development. Or had features deprecated without notice. Or watched Apple’s definition of “safety” crush creativity under a thousand human review rejections. Early VisionOS developers? Early victims of a failed ecosystem promised to them and ultimately temporarily put into stasis from abject failure.

Would you want to base your AI product on that - again?

The Parnas Point: Worth Heeding, But Not Holy

Parnas makes valid points about reliability, safety, and standards. But like many software engineers from a deterministic paradigm, he fails to see that LLMs live in a probabilistic world. They aren’t replacing command-line utilities. They’re augmenting cognition.

His arguments are important—but partial. To regulate AI like software is to misunderstand its nature. That doesn’t mean abandon caution. It means build new frameworks that match new frontiers.

Apple’s Catch-Up Problem: Can It Be Fixed?

Apple now finds itself in the humiliating position of having to buy its way back into the game. The rumours are swirling: Nvidia infrastructure, licensing deals, internal reshuffles, panic-mode hiring. Deals with Anthropic. You name it, there’s rumours about … But we’ve really seen nothing but Apple returning to the drawing board of 2023 reading for WWDC 2024, and having to re-position again to make an announcement at the upcoming WWDC 2025, skating to where the puck has been in more like a figure skating dance contest than strategic and tactical plays.

“So all of this activity? None of it guarantees success.”

The real problem isn’t lack of money or talent. It’s mindset. If Apple continues to see AI as a threat to be tamed rather than a tool to be trusted—one that grows with the user, not over them—then no amount of engineering will help.

“This is not a speed race. It’s a worldview shift. And Apple, for the first time, may have the wrong worldview.”

Why WWDC 2025 Is Critical

Apple’s theme this year—“On The Horizon”—could be interpreted two ways. Either as hopeful optimism… or as a quiet confession that what you’re looking for still isn’t here. And might not be for another year. Let’s call it smoking “hopium“ for now, until we see some results.

It has one shot to reclaim this space. To show not just a product, but a vision—one that integrates AI not as a feature, but as a philosophy. Anything less, and it risks losing not just relevance, but resonance.

The 15–25 year-olds are already using LLMs as cognitive exoskeletons. They are building workflows around them. They are emotionally co-regulating through them making up for the speed at which the digital world works. Our poor brains’ lack of a neurotransmitter and neurology regulator evolution has not kept up with today’s exponential demands of it, and instant answers to complex questions are increasingly not just desirable, but necessary, for people to keep up with it . Today youth and younger adults aren’t waiting for the puck. They’re already skating circles around it, while boomer armchair generals argue about whether the odd “hallucination” might be just unacceptable, “unacceptable and useless I tell you.”

The Final Question

What will Apple’s WWDC “On The Horizon” event actually reveal—and will it be enough, whenever it arrives, to meet the world where it’s already going?

“Because by the time Apple gets there… the puck may already be at WWDC 2026. Or worse—2027. By which point we might have all ditched our iPhones for brain implants courtesy of Sam Altman and Jony Ive.“

Welcome to tommo.fyi, where we call it when we see it—and usually before the earnings call, and always before Mark Gurman’s Sunday Ablutions.

- tommo 1st June 2025

fyi. There’s a good discussion of this going on at PED3.0

Subscription only site with a great commentator base and daily Apple and AAPL newsreel.