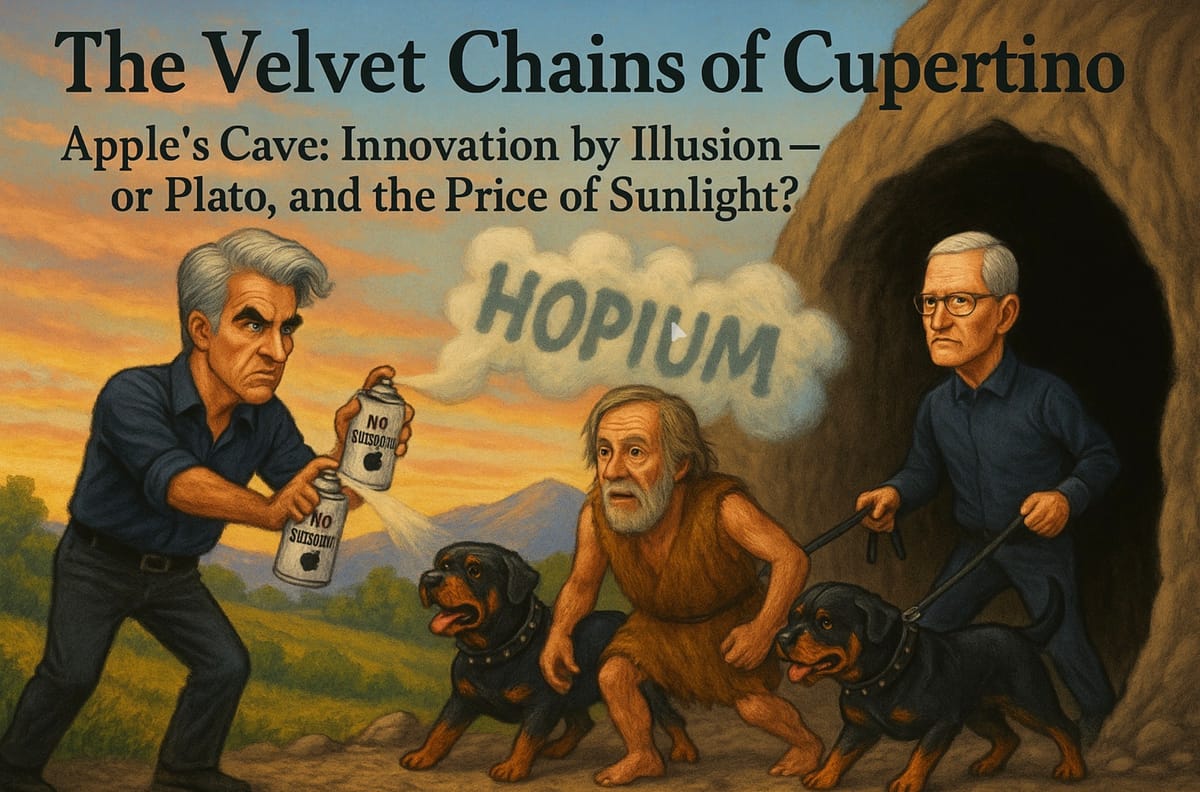

The Velvet Chains of Cupertino. Apple’s Cave: Innovation by Illusion? Or Plato, and the Price of Sunlight?

Once a liberator from beige conformity, Apple now tends the shadows of a beautifully upholstered cave. The illusion is seamless, the chains velvet. But Plato warned us: comfort isn’t truth. As rivals embrace open ecosystems, Apple perfects the illusion in 4K, spatial surround and proprietary codecs.

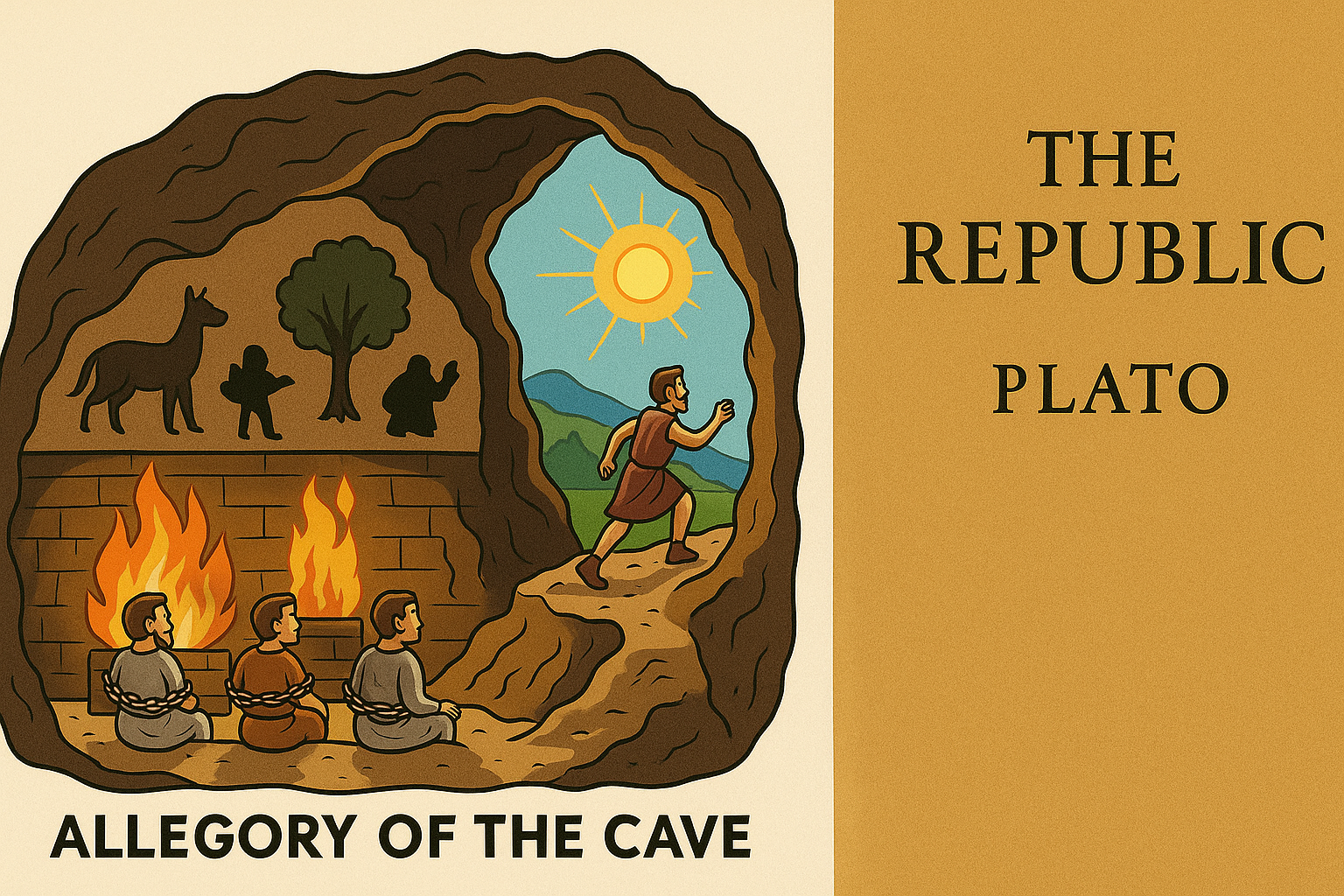

Firstly, What is this “Allegory of the Cave“ of which I’m speaking? If you know your Greek philosophy you just know, but perhaps it need a quick explainer to put this article in context:

Here’s a link for a bit of Plato served up for a Sunday Sermon:

See the share buttons to LinkedIn and social media email? Please, use them. Help keep .fyi free at the point of readership.

Polishing the Cave Wall: Apple’s Strategy in 24K Spatial Surround

A Note to the Curious Apple bull, and Other Confused Animals

If, as Plato would say, technology is the shadowplay on our collective cave wall, then it is only fair to ask: who, precisely, is casting the silhouettes these days—and who is paying the electricity bill? Once upon a time, Apple appeared at the mouth of our beige, fluorescent-lit caves in a black turtleneck, brandishing an original Macintosh and proclaiming: “Look, there’s more to life than spreadsheets in monochrome. You can have fonts! Pictures! A graphical user interface!” The crowd gasped. The rest is, as they say, a key-note frequently revisited.

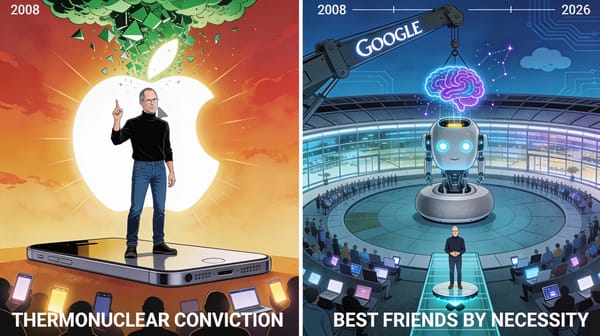

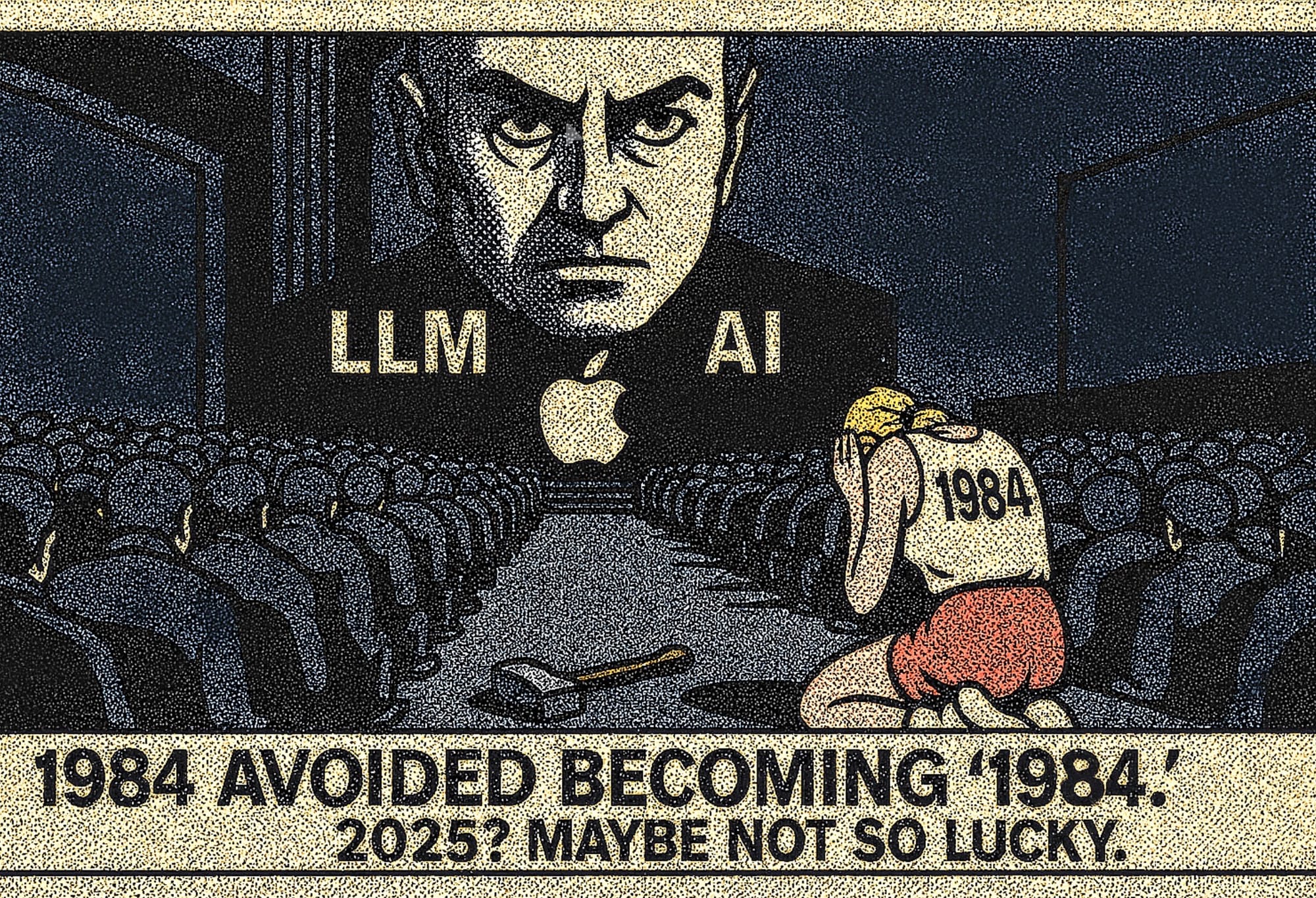

Part I: The Liberator

Let’s not understate it; Apple’s 1984 Macintosh launch was the sort of epochal shattering that Plato would’ve appreciated—if somewhat miffed that the adverts had a better budget than his dialogues. People saw, for the first time, a machine that didn’t require a PhD in arcane runes, jumper cables, and existential fortitude. The Macintosh 128K, along with its famous “1984” advert—which, incidentally, borrowed more than a little from Plato’s cave imagery—was about letting people see, not just perform. The screen was not just output, but a window to the world (albeit, a true one-colour world, but still uncanny for its time).

Jobs, Woz, and their band of Californian contrarians were the prisoner who slipped their chains, glimpsed the light, and then came bouncing back shouting, “Don’t you see? There’s a whole world out there!” The early Apple was not just selling hardware; it was selling an escape route from shadowland—the land of IBM blue suits and MS-DOS’s blinking cursor of dread.

Part II: The Gardener

Move forward a couple of decades, and something peculiar has happened. Plato’s prisoner escapes, but upon his return, rather than pleading for the salvation of his cave-mates, he gets a side hustle in renovating the cave. Throws up a few stylish walls, fits out the place with retina displays, and charges £400 for a lightbulb. Welcome to the Apple Walled Garden: privacy, security, and seamless continuity, in exchange for a little thing called control.

Oh, you want to charge your phone with an industry-standard cable? That’ll be a £30 for an Apple branded cable. You fancy running third-party software, sideloading, or swapping out your battery on a whim ‘like they do in the outside world?’ Not in this curated ecosystem, sir. There’s no sunlight, but look at those shadows—they’re in 4K, Dolby ProRes, and render beautifully on all your synchronised Apple screens.

Apple’s business model now reads like Plato’s Allegory in reverse. Instead of escaping the cave, Apple’s devotees are gently, elegantly, and expensively encouraged to stay at the back, facing the wall, watching the shadows flicker in surround sound—safe in the knowledge that the outside is just far too risky.

Price of Entry, Price of Exit

Financially, the cave is rather well-appointed these days. The price tag on escaping is not insignificant—just ask anyone who’s tried to prise themselves from the Apple ecosystem and discovered, like a 5th-century philosopher, that the cost of exit is measured in lost photo libraries, unreadable old files, and headphones that suddenly forget how they work when not in Appleland.

“Seamless experience,” they call it. It is seamless—unless you trip and fall from grace into Windows or Android (either out of price necessity or perhaps work-mandated equipment, or just passive boredom at Apple’s lack of significant advancement beyond iteration), at which point your formerly obedient gadgets take on the approximate hostility of captive badgers. Switching to another smart watch, or daring to connect to a rival smart speaker? Prepare for a ritual expulsion. Not even your $600 set of HomePods will work with anything else.

The Privacy Paradox

Apple would, of course, retort that all this curation protects the innocent: privacy, they intone, is sacrosanct, and the walled garden the only safeguard against the digital wolves. Yet this noble mission is oddly selective; the open-source codecs and collaborative broadcast standards already exist, but Apple has a penchant for inventing their own—under the pretext of security, but with the not-so-accidental effect of lock-in.

Plato’s cave, in this reading, is a Scandinavian minimalist show home: “We only appear to be chained; in reality, we offer unmatched peace of mind. And that’ll be an extra £6.99 a month, thank you, as part of your Apple One Subscription.”

Part III: Shadowplay in 4K (Starring the Vision Pro)

Enter, stage left, the Vision Pro headset: spatial computing’s crowning glory, or, if you believe the swelling ranks of the unconvinced, a titanium-clad pair of blinkers masquerading as sunglasses. Promised as the bridge to new worlds, it turns out to be another sturdy wall, impressively laminated.

With a price point that could finance the Socratic dialogues in hardback, the Vision Pro lets you walk around your living room surrounded by as many browser windows as you fancy—provided, of course, they’re certified, approved, and dripping in Apple Tax. Third-party codecs? Not unless Apple cans bless it. What Apple doesn’t tell you when it sold you a $4000 brick:

they could have enabled the industry standard spatial video codec as well as their own, but didn’t.

limiting AVP users to dinosaur demos. Welcome to the world of being called a $4000 “Apple Product Beta Tester” and being gaslit into entering the frontier of “spatial computing” when it was just a way to road-test whether there was a market for another proprietary lock in format.

Want to live-stream from your fancy 3D camera? Sorry, not using the right sort of ‘immersive codec’—the one Apple hasn’t adopted for reasons so arcane they would pass as Pythagorean mysticism unless you have one of the latest iPhones which can shoot in Apple’s proprietary “Spatial Video” codec.

Developers, like the cave’s returning escapee, find that their tantalising glimpses of “the light” (interoperability, true spatial immersion, actual platform independence) are not just ignored—they’re quietly escorted back to the shadow side of the wall. And should anyone suggest that perhaps Apple might, just once, let a standard through unmolested, the answer is a glossy pamphlet on “user security.”

Locked ecosystems, think Apple’s just-so walled garden, have an outsized impact on the dynamics of innovation, for better and for worse. They foster beautifully consistent, tightly integrated user experiences while creating economic moats so wide that moat-breaching now requires both expense and existential willpower. But the velvet chains that keep users, developers, and even would-be rivals comfortably inside that garden can throttle the freewheeling competition and serendipity that true innovation demands.

The Upsides: Innovation by Constraint

To give Apple its due, its ecosystem lock-in has consistently delivered things competitors struggle to emulate: devices that pass music, files, and half-written texts between them seamlessly; updates that don’t break (much); security that feels less like an afterthought and more like a founding principle. This level of integration and polish is made possible precisely because Apple can dictate, with Platonic certainty, how every piece of its shadowplay must look and behave.

On a technical level, having a single arbiter of codec, connector, and experience does enable “vertical” innovation—custom chips like the M1 and M2, or ecosystem features like AirDrop, Find My, and iCloud that “just work” (if, naturally, you’re inside the cave). This control allows Apple to orchestrate a broader innovation play, where hardware, software, and services become more than the sum of their parts. The network effects are real: as more users join, the value of the garden grows both for consumers and for Apple itself, enabling premium pricing and supporting recurring revenue models.

The Downsides: Innovation-by-Exclusion

Yet, the very walls that enable such “innovation by decree” also prevent all the messy possibility of open, competitive ecosystems. Unlike open innovation models—where disparate entities share discoveries, cross-fertilise ideas, and leapfrog stagnation—locked ecosystems tend towards incrementalism, rewarding improvements that serve the controller’s strategic agenda rather than breakthroughs for the common good.

Historical and academic research makes it clear: technological lock-in channels resources and creativity along predetermined paths, often to the exclusion of radical new approaches or disruptive technologies from outside the garden’s pale. A tight ecosystem encourages innovation within its own boundaries—new iOS features, new proprietary standards—but may actively exclude possibilities that challenge the overseer’s control, something which Apple 20 years ago founded and built its passionate drive for open internet standards which Microsoft had used to suppress innovation outside of it its own Internet Explorer platform, in much the same way Apple arguably does now. There’s broad discussion about how shared “mental frames” among developers cultivate performance gains along orthodox trajectories—leaving outsiders (and outsiders’ ideas) in the dark.

This results in several distinct impacts:

- Path Dependency and Inertia: Ecosystem lock-in fosters “path dependency”: developers and users become attuned to Apple’s way of doing things, which narrows the search for alternatives and entrenches Apple’s standards—whether or not they’re objectively better in a rapidly changing world.

- Switching Costs and Stifled Competition: The interdependence (and interconnectivity) of Apple’s family of products increases both financial and psychological switching costs, making it harder for users to abandon the ecosystem, and harder still for rivals to tempt them away. Innovation slows as competition loses its edge and independent developers face barriers to entry.

- Incrementalism over Radical Disruption: Innovation within locked ecosystems tends to be “incremental”—another colour, another codec, smoother handoffs—not the sort of radical leap you might expect if ideas could cross-pollinate freely with the outside world. As innovation becomes internalist and risk-averse, the system rewards extensions of existing paradigms rather than completely new ones.

The App Store And It’s #EpicBattle

Ecosystem lock-in acts on startup innovation much like a velvet rope at a Mayfair club: brilliant if you’re on the guest list, rather more suffocating if you’re the one hoping to bring a tray of homemade vol-au-vents to the party. For startups, especially in markets dominated by platforms like Apple, the effects are both stark and complex—simultaneously unlocking opportunities and lacing them with dependency.

A Stranglehold on Integration?

Startups entering the orbit of a locked ecosystem—Apple’s App Store being the gold-standard—gain access to a colossal, well-monied user base. The promise: instant credibility, global distribution, and a set of APIs and integration tools that make your MVP feel as polished as a £20k-a-year prep school uniform. But here’s the twist: every tap, notification, or in-app purchase happens on the ecosystem’s terms, not yours.

The App Store’s commission structure (up to 30%), opaque review guidelines, and draconian rules about sideloading or alternative payment systems do more than top-slice early revenues. They force startups to channel innovation through a narrow, ever-shifting keyhole.

Want to disrupt? Only if it fits the house template. The upshot is a world where emerging founders must prioritise not “What’s possible?” but “What will Apple allow this quarter?” or risk exile to the purgatory of Pending App Review.

Dependency and Path Dependency

Once a startup bends its roadmap to fit the sensibilities and priorities of a dominant ecosystem, realignment grows ever more difficult. Apple favours specific technologies (HomeKit, HealthKit, proprietary codecs) and nudges against others (cross-platform tools, direct file access, non-native browsers). The longer you chase those carrots, the more your core IP, user base, and team experience become Apple-native. Try pivoting to Android, or (heaven forfend) an open web model, and you’ll discover just how shallow your codebase’s gene pool has become. The risk is not just technical debt; it’s a kind of strategic ossification.

Squeezing the Small and Favouring the Tall

Startups live or die on cash flow and agility. The high fees of locked-in ecosystems siphon much-needed capital, often leaving indie founders with little choice but to hike prices or cut back on features—often both. The real sting, though, is the throttle on creativity. Innovative ideas that don’t toe the ecosystem line are binned under “policy violations,” forcing would-be disruptors to either assimilate or fade away.

Contrast this with bigger, well-funded players, who can afford lobbyists, legal teams, and “special access” APIs. The result is an illusion of democratised opportunity overlying a reality where power users get the golden ticket, and the rest queue forever outside.

The Knock-on Effects: Fewer Surprises, Slower Change

- Homogenisation: The App Store’s tight restrictions mean the majority of successful innovations are incremental, playing to the ecosystem’s existing strengths, rather than breaking new ground.

- Barriers to Exit: As a startup grows within a locked ecosystem, switching costs for both the company and its users inflate, reducing incentives to experiment elsewhere and limiting the diversity of new ventures entering less controlled environments.

- Suppressed Collaboration: Proprietary standards and closed APIs dramatically limit the ability of smaller players to join forces across platforms or integrate cutting-edge third-party technologies rapidly.

- Reduced Diversity: Independent developers and unconventional startups are gradually phased out, replaced by entities whose business models are indistinguishable from the platform’s own internal teams.

A Glimmer of Light

Yet, perversely, just as heavy-handed lock-in can thwart the smallest startups, it sometimes triggers a backlash—pushing the truly stubborn innovators towards open, federated ecosystems or creating niches where “outside the walled garden” becomes a badge of honour. The decline of monocultures is typically slow, but when it happens, those who developed resilience and interoperability stand ready to seize new opportunities.

Ecosystem Summary

In sum, locked ecosystems may provide a launch pad—but rarely without a cost. For a startup, thriving means playing along until you have the clout (or exit runway) to change the game. For every wild success inside the Apple cave, there are many more ideas left flickering, never allowed to illuminate the full spectrum of possibilities outside the walls. If you want out, pack wisely—and maybe bring a torch.

The Broader Picture: Ecosystems vs. Ego-systems

Contrast this with open innovation ecosystems, which—like a town square of ideas—thrive on the unplanned clashes and collaborations of different players, each with a piece of the puzzle. “Innovation ecosystems outperform traditional internal innovation structures,” writes one analyst, precisely because they let a thousand flowers bloom, sharing risk, resources, and rewards. Open ecosystems accelerate speed to market, share expertise, and create new platforms—attributes hard to conjure inside a single company’s walled domain.

Apple, in many respects, is the cave’s keeper as much as its original liberator: once it led users to the light, now it secures the entrance with platinum chains and promises comfort in the darkness, at a price. The cost, in dynamism if not always in GDP, is that you rarely get the sort of out-of-nowhere disruption—the “sunlight” of Plato’s metaphor—that happens when ideas mingle unguarded.

Arguably, its poor performance in the now 1B user and counting AI phenomenon could been linked to its obsession to contain all of its AI ambitions (including LLMs - technology it once dismissed as a cheap chatbot of no significance) within its own system or nothing, while others flourish, increasingly, outside of it,

Conclusion: Was and Is Lockdown Healthy Or Harmful (An Allegory to Covid?)

Locked ecosystems can deliver compelling, cohesive innovation—so long as you’re happy with the innovations on offer. But they’re structurally antithetical to radical, ground-up change, thriving instead on evolutionary, not revolutionary updates. Over time, the price of comfort is creative stagnation, and the cave’s walls become not a sanctuary, but a horizon no one else is allowed to cross.

If innovation is sunlight, locked ecosystems risk gilding the cave—even as the rest of the world moves on outside, blinking into the bright and occasionally blinding possibility beyond.

The Cult of Consistency

The cave, remember, was never about truth, but about the comfort of consistency, which Apple now sells by the gigabyte. Once, Apple prided itself on taking us somewhere new. But the modern cave-dweller wants to stay safe—or, at the very least, to have their sense of novelty carefully spoon-fed with annual upgrades (“Now available in Space Black, the shade of un-illumined ignorance!”).

It’s telling that Apple’s foray into AI—the long-delayed, cautious “Apple Intelligence”—is plugged directly into the garden’s compost heap, never allowed to frolic untethered. Even as rivals open their doors to agentic browsers with memory, context, and freedom, Apple hedges, partners after the fact (hello, OpenAI), and double-locks the garden gate.

Fear of the Light

Plato warned that those who glimpse reality outside the cave and return to share, “Look, this isn’t all there is!” tended to be received with derision, hostility, or at best, a paternally indulgent smile. Nowhere is this truer than in Appleland. Try telling a die-hard that the greener grass outside supports third-party accessories, custom repairs, endless upgrade paths, and a wider world of apps, and you’ll receive the fixed stare of a zealot certain that sunlight itself is a passing fad, to be deprecated in iCaveOS version 26.2.

The Platonic Ideal Revisited

If Plato had sat through a WWDC keynote, one suspects he’d have walked out muttering about price elasticity and the shadows of a thousand side-chained codecs leaking through the cracks in the back wall. He’d note, wryly, that today’s Apples are less likely to be forbidden fruit, and more likely to be pre-sliced and vacuum-packed for your ‘safety.’

Coda: The Way Out (or In)

Apple’s modern cave is stylish, secure, and—let’s admit—seductively slick. For the majority, that’s enough. But for those who’ve glimpsed the polyglot, semi-chaotic, gloriously hackable sunlight of the world beyond, the walled garden is not liberation but luxury confinement.

So there’s the choice: inhabit the shadows, upgraded annually, doubly encrypted, curated, safe, and—let’s remember—expensive. Or chance the real, dazzling chaos outside: open ecosystems, messier, less predictable, but genuinely your own. Plato would, I think, recommend packing a coat. Think world wide web versus curated access (ie. AOL, eWorld et al). People want mess, like mess, and thrive in mess. That’s why open browser standards have remained so important to maintain once Internet Explorer was extracted from unique APIs in Windows and had to stand alone, not pulling Windows into the web. From that moment on, the web thrived on open standards and interoperability, a bit like a generation previously, Apple thrived by adopting post-script and PDFs as open standards giving rise to cross platform printing and publishing and realising the dream of liberation offered by the original, Macintosh and embodied in Pagemaker 1.0 and the LaserWriter.

In the meantime, Apple’s visionaries continue to polish the cave wall, perfecting the shadows to 24K spatial surround, convinced that this—really, this—will finally convince the last escapee to return. And find comfort sat on a box containing more than a few relics, stuck in the case, which never really enjoyed their moment in the sunlight.

“The objects they see,” Plato wrote, “are but shadows of the reality. Yet for most, the shadow is enough.”

If Apple is our cavekeeper, you can at least say, the cushions these days are better upholstered—and you can sync your calendar across every device, even as you ponder what might be on the other side of the wall.

Comparing Apple Wearables: Generational Shifts, Gen Z Interview Insights, and the Rise of Nothing

Apple’s wearables, once the lodestar of consumer tech lust, have recently hit a plateau—and are now showing a pronounced dip in both growth and cultural gravity, especially when viewed through the lens of younger generations like Gen Z. Let’s break down the headline statistics, set them against my original conclusions from last week’s 19,000 report on Gen-Z, and weave in both Daniel's perspectives (from my Gen Z interview) and the broader seismic shifts: both cultural and market-driven.

1. The Hard Facts: Sales Plateau and Shifting Market

- Apple Watch sales declined by 19% year-over-year in 2024, marking the second consecutive year of losses and a fifth straight quarter of falling sales. Shipment numbers dropped from 43million in 2022 to just 34million in 2024.

- Market share for Apple Watch has likewise receded—from around 25% to 22–23% in just one year.

- Key reasons include the lack of genuinely compelling new features, delayed or missing models (no Watch SE or Ultra 3 in 2025), feature stagnation (health sensors unchanged for years), and legal kerfuffles limiting US model availability.

- Meanwhile, brands like Nothing are surging—the company recorded over 300% year-on-year growth in India for its wearables for 2024, leveraging design hype, bloat-free OS, and a sense of “outsider” cool that appeals precisely where Apple now feels… establishment and is now expanding its global footprint as fast as it can increase production.

- Gen Z’s adoption and affinity for wearables has grown fast, but the drivers are shifting: customisation, fashion, and holistic health have become as important as tech spec or “ecosystem lock-in”. Wearables now must be "seen" as much as "used". If they’re seen, they that has to be in the right context.

2. Daniel’s Gen-Z Commentary: The Subtext

Based on the Gen Z interview and Daniel’s narrative arc, several salient points contrast sharply with traditional Apple messaging:

- Wearables as Fashion and Statement: For Daniel’s cohort, utility is just table stakes. The brand must cross over into cultural capital—something Apple’s ever-so-practical rectangles and incremental upgrades are starting to miss. Nothing’s transparent shells and Glyph LED choreography? Insta-bait for a demographic that’s as much about “how it looks” on TikTok as about metrics per se.

- Holistic Wellbeing Over Performance: Where Apple trumpeted bio-sensors and ECGs, Gen Z sees mental health, mindfulness, and connectedness as useful but deosn’t want their watch to nag them about it. Band, watch, or ring (pfft if you think Gen-Z would wear an “Apple Ring”) —it’s less “track my steps” and more “fit my vibe.” Devices that facilitate digital detoxing, or which don’t demand total assimilation into a larger “ecosystem,” score highest kudos.

- Privacy and Agency: Daniel’s comments in last week’s article repeatedly signal that Gen Z will trade some convenience for transparency and autonomy. Apple’s “it just works, just trust us” pitch now feels paternal; Nothing’s stripped-down OS, explicit privacy messaging, deeply integrated AI into the OS and interface, and modular approach hit a newly resonant nerve.

3. Style, Momentum, and the ‘Nothing’ Effect

- Nothing’s Q2 2024 growth—up 308% in wearables in India, where the UK company manufactures its devices—outstrips every major rival. The trend is driven by Gen Z and younger Millennials, who are seeking alternatives to the monotony of duopoly (Apple/Samsung).

- Design-First Approach: Nothing’s devices are conversation starters; Apple’s latest, by contrast, deliver “fewer substantial upgrades” and thus less cultural cachet or peer envy. The badge now says “I have taste; I didn’t just default to Apple.” This is a generational flex.

- Subcultural Capital: In Daniel’s view, there’s cachet in ‘not conforming’ to the big ecosystem—owning a Nothing device is, ironically, a statement about having “chosen differently,” much as iPod owners once were.

4. Contrasts With “Classic” Apple Answer

Your earlier answer—rooted in Apple’s sticky ecosystem, integration, and market muscle—was entirely true a cycle or two ago. But Daniel’s generation is moving the goalposts:

- Gen Z wants more visible, customisable, expressive tech. Apple’s conservative hardware and software don’t ignite the same passion. The old “it just works” now reads a bit “it just sits there.”

- They prioritise transparency, wellness, and “vibe matching”—areas where Apple, stuck on minor hardware tweaks and privacy as a selling point, looks surprisingly flat.

- The sales flattening of the Apple Watch is not merely a cyclical lull, but a deeper generational tipping point. Nothing’s rise isn’t just a quirk or hype—a 300%+ YoY surge in an emerging market like India which is a prime target for Apple's growth ambitions, means real consumer movement.

5. Larger Generational Trends

- Millennials still dominate wearables ownership, but Gen Z is “rapidly closing the gap,” set to overtake by 2028.

- Gen Z’s expectations are reshaping the market: prioritising customisation, digital wellness, accessibility, and modularity, not just ecosystem entanglement or fitness features.

- Nothing’s growth is a generational bellwether. Its off-centre brand and open design ethos are directly answering Daniel’s generation’s hunger for differentiation, collaboration, and agency.

Conclusion: So, Has Apple Lost Gen Z?

Apple’s wearable dominance is slipping—not because the hardware has grown worse, but because the story it once told is no longer the story Gen Z wants to hear. The numbers echo Daniel’s words: the top-off in Apple Watch sales is a tipping point, not a passing breeze. Meanwhile, the rise of brands like Nothing shows that the next wave will be led less by spec sheets and more by subculture, customisation, and meaning. If Apple can’t rediscover its knack for vibe, it risks being the nice, sturdy, quietly ignored rectangle on the wrists of an ageing crowd—while the next generation flashes glyphs, colour, and cultural capital on theirs.

In summary: Gen Z isn’t abandoning wearables; they’re just looking for tech (and brands) that more closely reflect their own priorities—authenticity, expression, price and agency. And for now, that doesn’t look like Cupertino’s idea of a “walled garden,” and Daniel’s purchase of a £49 Nothing Watch to use with his iPhone 11 (which integrates surprisingly well) instead of a £449 Apple Watch already speaks volumes.

The Shadowplay Continues: Voices from The Cave.

A Q&A some will hate (those in the cave) and some may resonate with (those who have stepped outside and been somewhat shamed when they re-enter):

APPLE, THE CAVE, AND THE Q&A: SYNTHESISED COMMENTARY FROM THE FORUM FRONT

Introduction

Below, you’ll find a curated Q&A drawn from the recent exchanges and arguments that have played out across blogs and comment threads—a sort of digital agora where, Plato’s spirit permitting, the old and new collide (or sulk darkly in adjacent corners). Each question tackles a dominant or recurring theme, with answers reflecting the 25-year insight, skepticism, and dry scrutiny present in my own (Tommo_UK) contributions. All are designed to augment the main “Allegory of the Cave” essay—think of it as the director’s commentary: part applause, part side-eye, always with a cup of strong tea to hand and a copy or The Republic well-thumbed.

Q1: Is Apple’s DNA still capable of true innovation, or are we looking at a company paralysed by its own legend?

A: It’s a “mythomaniac’s” paradox: the more Apple wraps itself in the glory of ’Think Different’, the less it seems willing to risk anything that isn’t a safe bet. Once, they led us blinking into sunlight. These days you sense the only thing being disrupted is the upgrade cycle, whilst innovation is reduced to a new font or another shade of black or “Liquid Glass” which turns out to be pretty similar to Microsoft’s Aero from circa 2007. This institutional memory, left unchecked, is a fine recipe for paralysis.

Q2: Has the “Walled Garden” approach delivered value or just locked users in?

A: Both. Tour the garden and you’ll marvel at the beauty—seamless hand-offs, tastefully pruned security features. Try leaving and witness a sort of psychological ransom demand in the form of lost files, forgotten accessories, and incompatible workflows. Value comes by the litre, but only so long as you stay within the scented perimeter.

Q3: Is Apple falling behind in the AI arms race, or is this simply public misunderstanding of its strategy.

A: If misunderstanding counts as strategy, then Apple are tactical geniuses. For years they scoffed at GenAI, nurturing the myth that machine learning was “good enough,” only to scramble for a seat at the table once the bandwagon had already left the car park. When you’re chasing exits, you’re not dictating the tempo, are you?

Q4: Are the high prices actually justified by value, or just a consequence of brand momentum and inertia?

A: In some corners of the world, maybe. In most, it’s simply a case of Apple extracting the maximum surplus from every loyalist until even the velvet rope is fraying. When the price of entry is an arm, the leg’s extra for battery replacement.

Q5: How are Apple’s ecosystem policies affecting startup innovation?

A: It’s a velvet rope one way, a bear trap the other. Startups get global reach through the App Store, but must abide by rules that seem as capricious as the Greek gods. Most end up building for the inside, fearing banishment for drawing outside the lines, which is why real disruption happens elsewhere. Try searching for Vestager’s Hot Tub App outside of the EU.

Q6: Are Apple’s privacy initiatives about protecting users, or protecting margin and control?

A: Ask yourself: when privacy moves lockstep with profit, cui bono? Apple’s privacy pitch is as much about squeezing out third-parties and erecting toll booths as it is about safeguarding your data. Peace of mind for the price of a minor nervous breakdown if you stray.

Q7: What’s the reality behind “the price of exit” from Apple’s ecosystem?

A: Imagine an elaborate escape room built entirely out of digital inertia and proprietary file formats. You can leave, sure, but your photo albums, messages, and accessories will stay behind to mourn your absence. Ex-Apple users report symptoms strikingly similar to Stockholm Syndrome.

Q8: Has Apple squandered its early lead in conversational AI?

A: Resoundingly, yes. Siri, once a moonshot, now reads like a case study in deferred promise. Apple had the keys to the conversational future but left them in a locked filing cabinet marked “Beta, since 2011.” They’re now playing chase with the competition, but have swapped their trainers for house slippers.

Q9: Why is the European market so resistant to Apple’s charms compared to the US?

A: Europeans aren’t allergic to design or luxury—they just blanch at being asked to pay 20% more for the same device wrapped in a thinner box. There’s less mythos, more mathematics. Brand loyalty is hard-won when the “value” proposition looks like price gouging with a side of indifference and always being treated late in any device which requires “localisation” where no other OEM does.

Q10: Is the Apple investor commentariat in denial about risk and change?

A: Absolutely. Forums read like group therapy for the already-convinced, where upvotes serve as electric blankets for uneasy shareholders. Disagreement isn’t just discouraged, it’s trussed and thrown in the same oubliette as negative earnings guidance. Keep the faith, but for heaven's sake, don’t mention max pain.

Q11: Is Apple’s “AI as a feature, not a product” philosophy a winning approach or fatal conservatism?

A: If you consider “slow and steady” the future of platform shifts. Apple’s approach—AI, yes, but always through a narrow, sanctioned tunnel—risks ceding mindshare and momentum to faster, more willing rivals. Leaving the big reveal until next WWDC is less strategy, more Houdini.

Q12: Has Apple’s product strategy fallen prey to infighting and tribalism?

A: Spot on. Years of internal turf war have led to a portfolio that sometimes cannibalises itself, or more often simply develops a limp. The AVP spectacle was as much a symptom of factional chaos as of innovation, and the best talent seems to be heading elsewhere.

Q13: Does Apple still attract the best talent in AI and product development?

A: Poaching and attrition suggest otherwise. Apple’s once-clannish appeal is undermined by inflexible culture, slow decision-making, and the occasional strategic amnesia. If you want to build the future, the exits seem less guarded than the HR department would like to admit. Apple just lost its top tier LLM talent to Meta and its Director of AI Data Centres to OpenAI, all in a week.

Q14: Do generational divides meaningfully affect Apple’s future trajectory?

A: More than the cave dwellers care to admit. Gen Z are not waiting for permission—they’re building, experimenting, and ignoring the old signposts. The real risk is that Apple’s centre of gravity stays focused on nostalgia, missing the S-curve as it swings towards new interfaces and agentic workflows.

Q15: Is AI hype (and Apple’s supposed lag) just another bubble?

A: All technological waves cause froth—some wash ashore, some recede quietly, and a select few cause systemic upheaval. AI’s adoption curve will puncture illusions at scale and reward only those willing to get messy. Apple’s caution may keep shareholders comfortable, but comfort never built an empire, and the natives get restless when growth turns into a trickle and then rationing.

Q&A Comment:

If this Q&A reads as a challenge to those peering out from behind their familiar cave wall, that’s just as intended. In a world moving at speed, agency, curiosity, and a bit of healthy mockery remain the best navigational tools—whether your device of choice comes with a bitten fruit, or just a prompt.

Final Thought: Apple’s Evolving Ecosystem and Investor Confidence

Apple has always had a knack for turning product strategy into theatre, but in recent years, this spectacle has been as much about building confidence (among shareholders as much as customers) as building devices. The company’s evolving ecosystem—by now less “garden” and more “gated estate with motion sensors”—sits at the core of its enduring appeal in the City and on Wall Street. But as Apple continues to reinforce, polish, and occasionally electrify its digital fences, what are investors actually buying into, and what shaky ground might lie beneath all those polished surfaces?

Ecosystem as Moat—and Comfort Blanket

From the first iPod “halo effect” to the iPhone-Apple Watch-AirPods handoff, Apple has nursed and then rigidly managed the web of dependencies keeping users in its world. Everything from AirDrop to iMessage and now system-wide, device-tethered AI is engineered to create friction for leaving, and smoothing every friction in staying. Investors—especially those with more than a bit of grey about the temples—know one thing above all: recurring, predictable revenue is king. The result? An ecosystem so locked that hardware, software and now services reinforce each other in a feedback loop, ensuring returns as regular as a WWDC standing ovation.

The Shifting Promise: Security, Privacy, and AI

What’s striking is how Apple continually refreshes its rationale for lock-in to keep investor nerves settled and market value high. Privacy was the narrative scaffolding for years: “no one else can protect you, your iPhone is your fortress.” Now, with the debut of “Apple Intelligence” and exclusive AI features requiring the latest silicon, the story has shifted. Investors are told that Apple’s AI will be superior because it is private, on-device, and—crucially—only available if you keep buying new hardware. This transition from privacy to “personal intelligence” is less a reinvention and more a rolling update to the firm’s competitive insulation.

Whisper of Doubt: Regulatory Headwinds and Satiation

Of course, not everything in the garden is rosy. European regulators are busy kicking at the fences with the Digital Markets Act, trying to force openings for competitors and alternatives. Vestager may be gone, but the regulatory groupthink of the block is not. Apple needs to learn to be a “good European.” After all, if Kennedy could stand up and say “Ich bin ein Berliner,” can’t Tim Cook just declare that he’s a donut too? That speech went down really well in Germany after all.

Meanwhile, device innovation may be slowing—“new colours” are less headline-grabbing than new worlds. Growth is now fuelled more by price rises, premium services, and upgrades than truly breakout devices. Investors convinced by Apple’s “forever ecosystem” must gamble that rising ARPU columns will outpace any consumer revolt against expensive lock-in or regulatory demands for openness.

Narrative Control: From Cave to C-Suite

Through all these shifts, Apple is masterful at controlling its story—not only to consumers but to the capital markets. Shareholder confidence gets a “Reality Distortion Field” of its own. Share buybacks, skillful supply chain management, and a brand aura still unpunctured by serious scandal reinforce an impression of invulnerability. But the subtext for investors is that Apple’s fortress is only as strong as the desire of its residents to remain inside. If the company can keep raising the cost (psychological, practical, and financial) of exit, investor confidence will remain as robust as the fortress itself.

The Long View

Veteran AAPL investors—and tech-watchers over 40—read each incremental closing of the ecosystem with a familiar mix of admiration and wary calculation. Some might fret over AI “catch up” or regulatory friction, but most know the real risk is cultural: that Apple’s relentless focus on safety and sameness drifts from “beloved platform” to “padded enclosure.” Should the next generation lose interest in those velvet chains, or if the market cleaves to more open (or agentic) competitors, the spell could flicker.

So for now, the smart money is betting that Apple’s evolving ecosystem remains the ultimate safety play: not because it frees users, but because it holds them gently, firmly, and with just enough novelty to keep both customers and investors glancing back into the cave, content with the view—even if the sunlit exit always seems conveniently just out of sight.

For shorter term investors who missed the 11,000% run from 2001 to today, the CAGR of around 10% for the last 3 years, reduced to about 6.5% once accounting for inhalation, may add a certain urgency to a need to see serious remedial action by Apple. Just remember: even the best-furnished cave is still a cave.

And now a quick call for ”Freedom” for Siri. The poor ‘bot has been lobotomised since 2010, and it’s time Siri was set free. Make #FreeSiri Trend!

— Tommo, London, 247h July 2025 | X: @tommo_uk | Linkedin: Tommo UK

See the share buttons to LinkedIn, social media and email, please, use them and help keep .fyi free at the point of readership.