The Vision Thing: Why Execution Is the New Charisma And What Lessons Apple Could Learn From it’s Past.

There’s a moment in every great story where dreams become tangible. The sketch on the napkin becomes the prototype, and the prototype becomes the product that changes everything. But we’re living in a tech world that increasingly forgets that middle step. Vision is everywhere. Execution is MIA.

I’m not a cynic. I believe Apple can still deliver the next boom. I believe Apple Intelligence — if executed well — could redefine the interface. But belief isn’t the same as trust. And trust has a deadline. So here’s the Sunday benediction:

“Don’t show me your North Star. Show me your calendar.

Because vision is cheap. Execution is everything.”

And real artists still ship.

UPDATE: THE ORIGINAL VERSION PUBLISHED REVERTED TO DRAFTS AND SADLY HAD SOME INCOMPLETE SENTENCES AND TYPOS IN IT. SOME OF THESE HAVE BEEN HASTILY FIXED, BUT IN 10,000 WORDS, SOME REMAIN. APOLOGIES FOR THIS; THE CRASH LEFT A RE-WRITE NEEDED, BUT LIKE STEVE SAID, GREAT ARTISTS SHIP, SO HERE IT IS, WARTS AND ALL

So where did that quote come from? Context:

Bud Tribble was one of the original members of the Macintosh team and served as software manager for the project. He was instrumental in helping define the early Mac UI and bringing the ideas of graphical computing to life, working closely with both Jobs and Jef Raskin.

The “real artists ship” quote came in the intense final stretch of the original Macintosh project, when the team was struggling with feature creep, last-minute changes, and Jobs’ famously perfectionist tendencies. According to various oral histories (including Andy Hertzfeld’s Folklore.org), Tribble was pushing for more time to polish certain elements, and Jobs—while a perfectionist himself—was reminding the team that deadlines matter, that products must exist, not just aspire.

The full paraphrased moment:

Jobs was trying to draw the line between endless polishing and actually putting something in the hands of users. When Tribble advocated for more time, Jobs responded: “Real artists ship.”

— Steve Jobs to Bud Tribble, ~1983

Meaning:

Jobs was reframing the idea of creative excellence. He wasn’t dismissing quality — he was challenging the myth that endless iteration = greatness. To him, execution was part of the art. Shipping, despite imperfection, was the signature of a true builder. It became one of the cultural pillars of Apple under Jobs both before and after his return.

ACT I: THE SHIPWRIGHT’S CODE (1983–2007)

The first thing Jobs ever shipped wasn’t a product. It was a standard. A mandate. A refusal to be the guy polishing the prototype while the world moved on. “Real artists ship” wasn’t just a zinger — it was the operating system of a company that would become the most valuable in the world. But not because it had the best ideas. Because it shipped them.

1983: The Original Pirate Flag

In 1983, Jobs raised a skull and crossbones over Apple’s Bandley Drive skunkworks. The Macintosh team weren’t just employees — they were pirates. This wasn’t cosplay. It was a rebellion against the bureaucratic torpor infecting the rest of Apple. Jobs knew the disease of delay. Of committees. Of compromises that never reached escape velocity.

The original Macintosh shipped in January 1984 — underpowered, overhyped, and profoundly flawed. But it shipped. That act alone changed the course of the company. Because once it was out in the world, it forced the feedback loop. It compelled iteration. The second-gen Mac (512K “Fat Mac”) came less than a year later. The LaserWriter and AppleTalk followed — and with them, the desktop publishing revolution.

In other words, flawed shipping begat strategic dominance. The Mac didn’t succeed because it was perfect. It succeeded because it was there — and because Jobs used the shipping act itself as a forcing function to build the next thing faster. That’s the Shipwright’s Code. Get it in the water, then reinforce the hull.

QUOTE CONTEXT: “Real artists ship” was delivered in typical Jobsian frustration — Jobs was furious the original Mac team were stuck tweaking icons while deadlines slipped. But the subtext was clear: The market doesn’t wait for elegance. It rewards presence. Get it out. Improve later. Own the cycle.

2001–2004: iPod and the Weaponisation of Iteration

When the iPod launched in October 2001, it was mocked. Five gigs. Mac-only. $499. And a FireWire port no one used. Critics scoffed: “Just buy a CD player.”

But Apple didn’t care — because they shipped. And then they shipped again. In 2002, the iPod 2nd gen arrived. Then iTunes stormed the market for actually managing downloaded music striking deals across studios and dominating the market for a “music store.” iTunes for Windows detonated the walled garden and doubled the market overnight. By 2004, the iPod Mini debuted — half the size, lower price, in candy colours. And the market tilted.

Jobs didn’t win the MP3 war with specs. He won by compressing the feedback loop into a weapon. Each generation was a correction, not a perfection — a move toward what people would want next, not what they said they wanted now. He didn’t wait for the perfect product. He taught the market to chase the ones he was shipping.

This wasn’t iteration. This was Blitzkrieg.

By 2006, Apple had annihilated every competitor — from Sony, to the Rio to Creative Labs — not because the iPod was unassailable, but because no one else could match Apple’s shipping cadence. The Shuffle. The Nano. The Touch. The U2 edition. It wasn’t a product line — it was a psychological pincer movement. They executed the competition off the field by moving faster and shipping smarter.

Jobs said: “You can’t just ask customers what they want and try to give that to them. By the time you get it built, they’ll want something new.” The corollary was: So ship what they don’t yet know they need — and ship it before they know to ask. That was the iPod’s doctrine. Unlike the Apple we know now, launching vanity projects like an overpriced AVP at $4000, Jobs’ time in the wilderness between his times at Apple had taught him the value of respecting not just his design excellence, but the need to make that excellence both affordable and appealing to a market taken by surprised but delighted and the awe he delivered.

2007: The iPhone — A Ten-Year Execution Strategy Disguised as a Joke

When Jobs took the stage in January 2007 and announced a full-screen iPod, a phone, and an internet communicator, most people thought he was joking. The iPhone’s price? $499. Carrier? AT&T-only. Apps? None, except the ones filling less that half the screen. The stock dropped after the reveal.

But Apple didn’t blink. Because Jobs understood something the market didn’t: the value isn’t just in the vision — it’s in the shipping. iPhone 1.0 wasn’t meant to win on specs. It was a land-grab. A vanguard. A “good enough” product that would force the world to respond while Apple silently locked up the supply chain behind it. And his announcement he’d capture 1% of the market within the first year? Modest to everyone who took one look at his vision and understood it, comical to Motorola, Nokia and BlackBerry executives who scoffed and sent one another message of mutual support the way drunks in the street proper one another up before being mown down by an oncoming lorry (truck, depending on your English).

That’s what Cook did for Jobs — striking exclusive deals for unwated 2.5” hard drives Jobs realised could support his original iPod vision then NAND flash chips, displays, rare earths. It’s what Ive did — iterating the form factor to support 3G, thinner batteries, better glass. By 2010, they owned the entire category. Android wasn’t just catching up — it was running uphill against gravity.

From iPhone 3G to 4 to 5, and then to the much loved thin and larger iPhone 6 and 6s, Apple shipped with military precision. That’s the part people forget. It wasn’t the iPhone 1 that changed the world. It was the certainty of the next iPhone. The ritual of shipping. Jobs turned launch day into the new Christmas.

Jobs once told Walt Mossberg, “We don’t get a chance to do that many things, and everyone should be really excellent. Because this is our life.” But excellence, to Jobs, didn’t mean perfection. It meant shipping something great enough to earn its sequel. “Great artists ship.”

Pattern Recognition: The Execution Flywheel

Let’s pull the thread tight.

• The Macintosh shipped too early. It needed a second act (and third). But it created a category.

• The iPod shipped narrow. But then it fanned out, crushing rivals through iteration.

• The iPhone shipped underwhelming. But it was a Trojan Horse for a decade of strategic expansion.

In each case, Apple didn’t just ship. They committed to the cadence. That was Jobs’ true art. Not just inventing. But executing — fast, relentlessly, and visibly.

And that’s what’s missing now. Not just the launch. But the loop.

ACT II: NEWTONS AND AIRPODS — SHIPPING WITH (AND WITHOUT) PAYOFF

“SOMETIMES WHEN YOU INNOVATE, YOU MAKE MISTAKES. IT IS BEST TO ADMIT THEM QUICKLY.” — STEVE JOBS

Newton: The Glorious Premature Child

In 1993, Apple released the MessagePad, the first product under the “Newton” brand. A handheld device with handwriting recognition, wireless comms, and data syncing — a vision ten years too early. Priced at $699 (roughly $1,500 in today’s money), it aimed squarely at mobile professionals who didn’t yet exist.

Its central idea was prescient: a digital assistant that travelled with you, learned from you, and kept your life in sync. Sound familiar?

But the technology wasn’t ready. The handwriting recognition became a pop-culture joke (thanks, The Simpsons). Battery life was terrible. Software clunky. Most damningly, the market lacked a bridge from Palm, Psion, or US Robotics to Apple’s new platform. People couldn’t connect the dots between the product and their need.

And yet… the Newton shipped. And by its third revision in 2000 — just after Jobs returned and euthanised it — it had finally become very good. The “failure” wasn’t technical. It was temporal. It landed on a beach before the customers had disembarked. And then was pulled from the shelves just as it got seaworthy.

CONTEXT: Jobs killed the Newton not because it failed to work — but because it broke his principle: ship, iterate, dominate. It had shipped. But Apple hadn’t committed. And without that commitment, the vision decayed. It didn’t dominate, but when it returned in the form if the iPad in 2010, he achieved his vision, his way, and dominated the market.

Vision Pro: The Newton Inverse

Fast forward 30 years.

The Apple Vision Pro launched in 2024 as a spatial computing platform — the supposed future of work, media, and collaboration. Priced at $3,499 (call it $4500 after accessories and custom lenses). No clear killer app. No App Store transformation. No iPhone moment.

But unlike Newton, the AVP had no organic demand channel. It wasn’t improving an existing paradigm (like PDAs or laptops). It was asking users to trade out the world itself — for a passthrough-mediated replica. It offered immersion in a world that, functionally, looked like a floating iPad. And for that, you had to strap a battery to your back and alienate everyone around you.

Where Newton failed but sparked a decade of mobile innovation, AVP failed with no runway beneath it. Apple positioned it like a dev kit, priced it like a Ferrari, and expected it to become the next iPhone. But products don’t become cultural artefacts because Apple says so. They earn it.

The core failure wasn’t the hardware — it was the failure to follow through. No content strategy. No developer ecosystem. No second model. As of mid-2025, inventory is gone, the launch version axed, the team disbanded, the consumer model has been delayed indefinitely, and Apple has yet to articulate a roadmap except for deploying the VisionOS team into trying to rescue Siri.

CONTEXT: The irony is sharp: Newton had too much purpose but not enough tech. AVP had incredible tech — and no purpose. One shipped prematurely but sincerely. The other shipped like a demo that slipped through marketing. Only one of them had Steve Jobs to kill it before it metastasised.

AirPods: Delay, Deliver, Dominate

Now rewind a little — to 2016. The AirPods were late.

Announced alongside the iPhone 7, they were supposed to ship in October. Critics mocked them: they looked like earrings, people would lose them, $159 was absurd. And then… “Apple missed Christmas.”

Except it didn’t.

AirPods landed in limited quantities on December 13, 2016 — just enough to ignite demand. Apple turned scarcity into desire. They sold out instantly. Videos of lines. Early adopters gushing. And suddenly, what had seemed laughable became inevitable.

But what mattered more was this: Apple doubled down.

• 2019: AirPods Pro — noise cancelling, better fit, another price bump.

• 2021: AirPods 3 — spatial audio, MagSafe charging.

• 2022: AirPods Pro 2 — personalized audio profiles, H2 chip.

What began as a joke accessory became a $20+ billion annual business, defined entirely by shipping early, fixing fast, and iterating constantly.

Unlike AVP, which cost 20x as much and still doesn’t justify a sequel, AirPods became Apple’s most successful new product since the iPad. Luckily, Apple haven’t g

Tim Cook, in a rare Jobs-like move, defended the early AirPods backlash by saying Apple “doesn’t chase market opinion — it shapes it.” But shaping it required more than launch theatre. It meant shipping and iterating until people couldn’t imagine going without them. Tim, sadly, seems lacking the confidence to offer quotes of such confidence any longer.

Newton vs. AVP vs. AirPods: Three Execution Archetypes

|

Product |

Vision Clarity |

Market Readiness |

Pricing Logic |

Follow-Up |

Outcome |

|

Newton |

High |

Medium |

Too high |

Weak |

Killed early, inspired future mobile |

|

AVP |

Low |

Low |

Absurd |

Unclear |

Zombie launch, unclear sequel |

|

AirPods |

Medium |

High |

Bold but fair |

Relentless |

Category-defining product |

Execution isn’t about perfection. It’s about shipping with enough purpose and momentum that the loop begins. Newton had purpose but no runway. AVP had neither. AirPods had just enough — and that was enough to kickstart dominance.

Execution Is Not the Same as Shipping. But You Can’t Execute Without It.

Every product in Apple’s history that succeeded had three things:

- It shipped with intent, not apology.

- It triggered follow-up iterations, not silence.

- It turned early flaws into late advantages.

Newton shipped too soon and died too soon. AirPods shipped late and flourished forever. Vision Pro shipped into a void — and stayed there, leaving only its OS behind to inspire new, future, iterations which should have preceded it.

In short: you can ship too early. You can ship too late. But you can’t win if you don’t ship again.

Act III: Garden Walls and Scaling Rivals

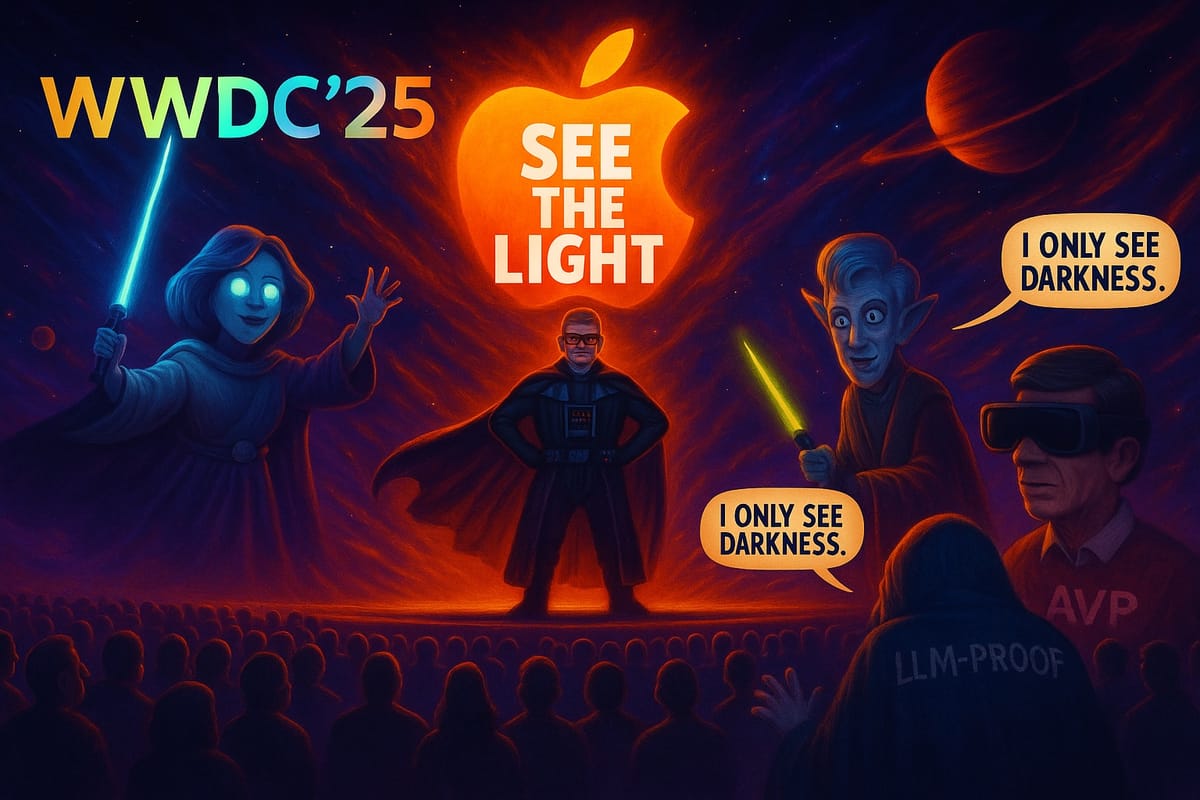

WWDC 2025 as Confession. The Climb Outside the Walls Begins.

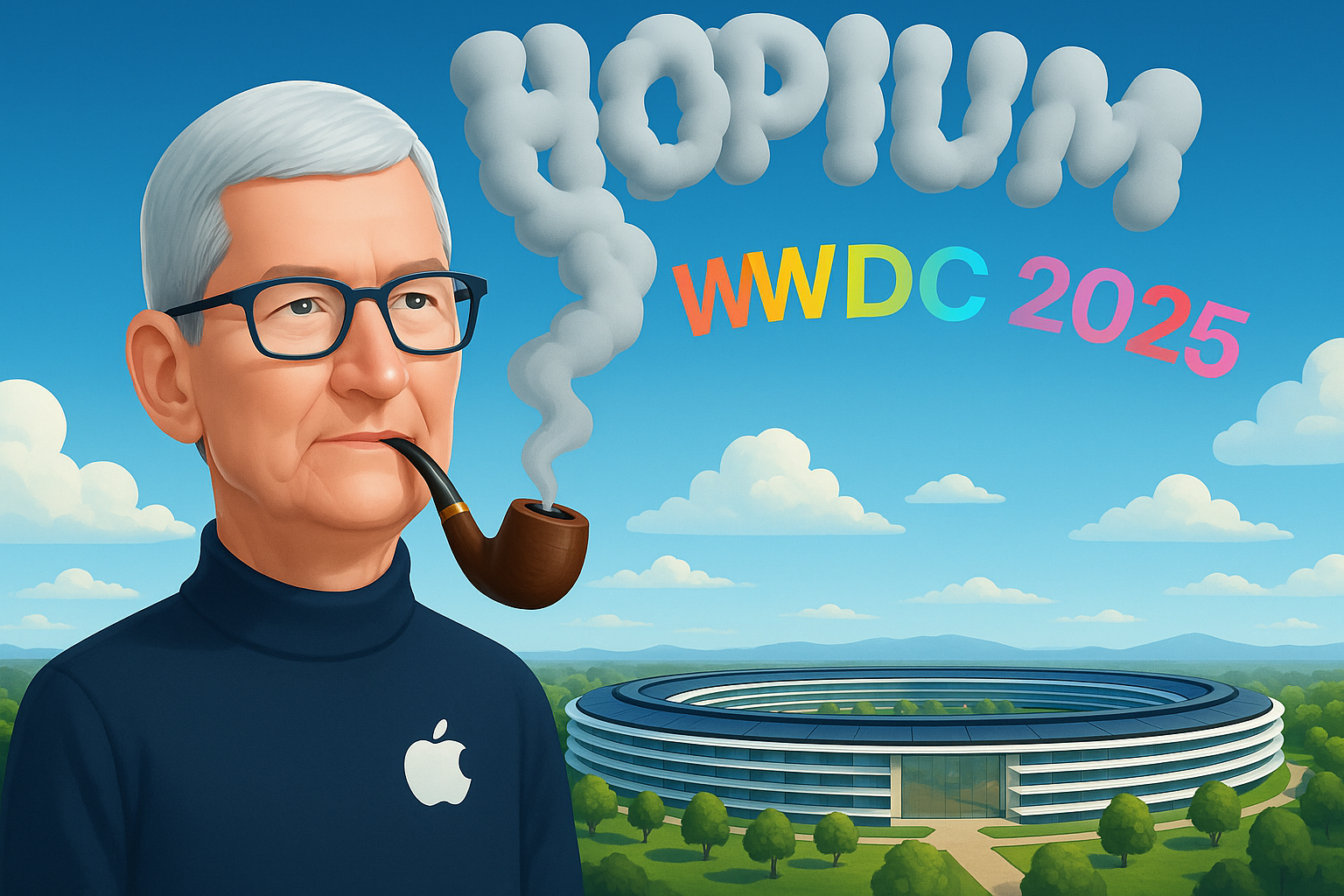

“Execution is everything” isn’t just a Jobs-era mantra. It’s the dividing line between Apple’s mythic past and its increasingly confessional present. And nowhere was that confessional tone more pronounced than WWDC 2025 — a keynote that promised AI magic and instead delivered… a two-year waiting list.

It’s worth revisiting what made WWDC 2025 so uncanny. The visuals were slick. The messaging was polished. But the vibe was unmistakable: apology disguised as anticipation. The AVP? Still boxed up. Apple Intelligence? Announced, but explicitly delayed. Siri? Promised, but postdated to spring 2026 — and even then, only as a preview. The signal was clear: the strategy wasn’t evolving. It was waiting. Apple’s LLM? 45 seconds and then never referred to again.

Meanwhile, the competition was scaling the garden walls. Not just chipping away — free climbing with chalked fingers and cracked knuckles. OpenAI, Microsoft, Google, even smaller agents like Rabbit and Humane — all flawed, sure. But shipping. Learning. Iterating. In the valley of visionaries, it’s the act of showing up that wins loyalty, not just the elegance of the pitch.

Here lies the deeper rot in Cupertino’s walled garden. For years, Apple’s tight integration and vertical control were its moat. Now, they’ve become a mirror. You can’t mirror what you don’t reflect — and in the absence of real-world output, Apple is mirroring itself. Carefully. Lovingly. Frictionlessly. But in doing so, it’s begun to orbit its own past, not escape velocity.

This wasn’t always the case. The iPhone’s launch in 2007 wasn’t just a product reveal — it was a dare. To bet on multitouch. To kill physical keyboards. To cannibalise the iPod at its peak. But it shipped. Then it shipped again, and again — iPhone 3G, 3GS, 4, 4S. Now we’re approaching the 17. Each cycle tightened the flywheel. Each launch taught competitors what not to bother trying. That’s what made the garden wall real — not rhetoric, results.

Contrast that with the post-2017 era. HomePod. Studio Display. AVP. AI. Siri Nouveau. The long-fabled Apple Car (Project Titan - more like Titanic). All hinted at. Some launched late. Others never at all. And those that did ship? Often arrived incomplete — unfinished by Apple’s own historic standards. The result is a pattern of unclosed loops. You can feel it in the keynote room. You can feel it in the AAPL chart which just rolled over and yo-yo‘d supported only by a PE which leapt from 18 to 28 as Apple revealed, with uncanny timing, the contribution Services made to its revenues and earnings. Apple would likely still be a $130-150 stock otherwise.

But here’s the real concern: Apple’s rivals are no longer trying to out-Apple Apple. They’re trying to out-ship it. Even Microsoft — the same company that once released the Zune as a cultural punchline — has found a shipping cadence in Copilot and Teams integrations that puts Apple’s AI ambitions to shame. They’re not waiting for perfection. They’re building presence.

WWDC 2025, then, wasn’t just a product event. It was a confession booth. A two-hour, high-gloss admission that the company had vision — but not velocity. That it had ideas — but not ignition. And in an age of accelerated feedback loops, delay is decline.

Apple’s garden still has beauty. Its devices still offer grace. But in a world of real-time agents, open ecosystems, and multimodal chaos, beauty alone isn’t defensible. Presence is. And presence can only be earned by shipping — not saying. Because in tech, walls don’t keep competition out. They keep the unshipped promise in.

“You can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backward.” — Steve Jobs, 2005

- In 2025, Apple isn’t connecting the dots backward or forward — it’s sketching outlines without delivering substance.

- This quote provides a reflective, Jobs-authored note that undercuts the current leadership’s detachment from historical cause-and-effect — shipping, iterating, then owning the future others didn’t see coming.

Act IV: Musk, Microsoft, and the Theater of Shipping

There’s a strange theatre to execution in 2025 — and the most absurd plays are selling out nightly.

On one end of the stage: Apple, immaculate, breathless, frozen. Perfectly spotlighted in announcements, stalling behind the curtain in reality. On the other: Elon Musk, bleeding, swearing, sometimes incoherent — but dragging half-built rockets and robotaxis into the light, flaws and all.

The contrast isn’t just about personality. It’s about shipping as performance art — and what that performance does to markets, mindshare, and momentum.

When Musk announced the original Tesla Roadster in 2006, the world scoffed. When he announced the Cybertruck in 2019, it was an internet punchline. In 2024, the Cybertruck still isn’t available in any meaningful volume — and yet it’s everywhere. It’s become a meme, a motif, a product that shipped precisely because it didn’t wait for consensus or perfection.

Apple would never have released the Cybertruck. Not like that. Not with those tolerances, not with that unfinished software stack, not with those lines. And that’s precisely the point.

Apple, in 2025, has become so preoccupied with the idea of seamless perfection — the illusion of the frictionless — that it’s forgotten what moving targets feel like. And in doing so, it’s ceded the most important advantage a tech company can have: momentum in the face of doubt.

Meanwhile, Microsoft — of all companies — has quietly stolen Apple’s script and started rehearsing it better than Apple does. Copilot didn’t arrive perfect. It wasn’t polished. But it arrived early, it arrived useful, and it arrived again a few months later — improved. It was iterative, humble, and fast. And it landed in Office, Teams, Windows — the products real people already use. In fact, it can run on your Mac and and it integrates with Office.

This is where Apple used to win. Not just by vision, but by distribution. By embedding delight where people already were.

Now it’s Microsoft doing it. While Apple delays Siri until mid-2026 and pretends the AVP is an “ongoing experiment,” Microsoft is giving teachers and accountants tools that help them now. Tools that improve monthly. That users brag about using. This is not to say Apple needs to become Microsoft. Or that Musk’s style of shipping is a healthy model. But in a world where chaos can go viral and iteration is rewarded — Apple’s elegance is looking more like inertia

Tim Cook once said: “We believe in the element of surprise.”

But in today’s market, surprise doesn’t mean unveiling a keynote demo. It means arriving in users’ hands before they even realised they needed you. Surprise now belongs to those who execute in public, and those who avoid their organisation leaking to the likes of Gurman’s ”My Apple Sunday Ablutions” column he writes for Bloomberg (from behind a paywall for some unearthly reason).

“Innovation is saying no to a thousand things.” — Steve Jobs, 1997 (WWDC fireside with Guy Kawasaki)

That was true. But today, Apple risks saying no to everything until it’s too late. The theatre of shipping — chaotic, glitchy, half-baked — has become the only way to stay in the story. Perfection doesn’t own the stage anymore. Iteration does. And iteration begins with shipping.

Act V: Vision vs. Volume — A Game of Timing

In Silicon Valley, timing isn’t everything. But it’s the multiplier. Vision without shipping is fan fiction. Execution without vision is enterprise software.

The alchemy happens when the two align — when a vision is shipped just early enough to feel bold, and just late enough to be usable. Apple used to own that fulcrum. Now it seems obsessed with winning the next cycle… by skipping this one, and saying it will evolve in time to skate to where the puck was last year, in time for next year.

Vision Pro is a parable. A headset born of brilliant minds, shipped into empty air. No mass-market tether. No defining app. No killer use case beyond tech demos and YouTube reviews. Compare that to the original iPhone: expensive, yes — but attached to a product people already used daily: the phone.

The iPhone didn’t ship into a void. It shipped into a need. And then reshaped the need.

The AVP shipped into a fantasy. And then… waited. While early AAPL buyers enjoyed buying $4000 goggles with their dividends, everyone else shrugged at the idea of buying something called “spatial computing” and decided to use a more familiar term from years of watching Star Trek: “A Spatial Anomaly.”

This is the same company that once released the iPod shuffle, a music player without a screen — simply because they could flood the market and dominate by ubiquity. It wasn’t a flagship. It was a follow-up. An execution play. The opposite of perfectionism. And yet: it worked.

Because once you ship, you earn the right to refine. To iterate. To build Gen 2, Gen 3, Gen X.

Just ask Nintendo.

The Nintendo 64 launched late. But it launched. Cartridges were scarce, logistics were dire — but you could buy it. And that alone meant kids would beg their parents, Toys R Us would catch fire with the traffic flowing through them, and competitors would just stare in shock, knowing then been Zelda’d all over again.

The PlayStation 2 was understocked, overpriced, overhyped. It still became the best-selling console of all time. Why? Because it shipped. Even in dribs and drabs, it existed. And in doing so, it rewired desire.

The Xbox 360 beat the PS3 to market by a year — even though its early units were plagued by red-ring failures. But it won the cycle. Why? Because it showed up. And it kept showing up. Microsoft bet on momentum over polish — and that bet paid off.

You could argue the Model 3 did the same for Tesla. It wasn’t on time. It wasn’t flawless. But it was relentless. It kept shipping. And that created belief.

Apple knew this once. When the iPhone launched, the first year was messy. It lacked 3G. It had no App Store. The price dropped $200 in 90 days and sparked backlash. But it shipped. And the feedback loop it unlocked created the App Store, the SDK, the A-series chips, the multi-device flywheel.

All of that — because they shipped.

In contrast, Vision Pro has paused. It’s waiting for the world to catch up. But the world no longer waits. The world adapts to what shows up.

Execution isn’t the tail end of vision. It’s the beginning of reality. And every delay you justify with “strategic patience” is a user not using your product, a developer not building for your platform, a competitor not standing still. Apple now feels like a company afraid to ship anything it can’t narrate perfectly in advance.

But in 2025, the winners are the ones who ship, learn, and revise — not the ones who storyboard the future in twelve acts. Apple did that in 2024. It flopped. It’s now saying in 2025 it will succeed in 2026. The world is interested, but with AI and other phenomenon developing at light speed around them, the interest is more passing than hyper focus. Apple watching has become a bit like bird watch watching, for the few, not the many

“The way to get started is to quit talking and begin doing.” — Walt Disney

That’s what Apple used to believe. You started with a product. Not a plan.

You revised with users. Not internally with slides. You earned iteration. You didn’t simulate success in keynote format. In a time of AI-native startups shipping features weekly, “coming next year” is not just a delay. It’s a loss of tempo. It’s a vacuum and someone else will fill it if you don’t.

Act VI: Companies That Shipped — And Why It Worked

Let’s break the Apple trance for a moment.

This isn’t a morality tale about one company losing its way. It’s a broader parable about what happens when companies forget the sacred law of velocity: you ship, or you slip. While Apple has been workshopping metaphors, others have been moving markets or even re-defining them while Apple backpedals furiously.

Nintendo is the high priest of imperfect launch strategy. The N64 shipped with supply issues so dire you had to cold-call rural stores in other states. But it shipped. And that act alone generated a hunger that no press release could fake. Scarcity wasn’t a flaw — it was fuel. The GameCube followed suit: underpowered, purple, and still a fan favourite. Why? Because Nintendo never mistook polish for presence. They showed up, often oddly — but always memorably.

Sony’s PlayStation 2 launched understocked and overpriced. It had DVD playback and hype — and little else. But the halo effect of simply being there cemented its position before Microsoft and Nintendo could respond. It shipped, it sold, it won.

The PS3, in contrast, over-engineered itself into delay purgatory. The result? Microsoft stole a march. Which brings us to the Xbox 360: an example of execution over elegance. It launched before it was ready. Red Ring of Death was real. But Microsoft owned the generation because they prioritised presence. They knew that in the console wars, momentum beats perfection — every time.

Even Meta — hardly a paragon of taste — understood this with the Quest 2. It wasn’t sleek. It wasn’t lightweight. It wasn’t even particularly well-designed. But it shipped. And in doing so, it staked a claim on VR before Apple’s headset was more than a rumour, and they have kept up that imperfect momentum with their collaboration with RayBan for AR glasses.

The Quest 2 created a feedback loop. AVP created a showroom. Apple should have had its usual second mover advantage and dominated eye wearables and AR glasses. Instead, we got a $4000 pair of over-spec’d technological marvel ski goggles nobody wanted, and an enormous missed opportunity of such magnitude and delayed so long it’s safe to say it has probably squandered hundreds of Billions of market cap off Apple’s value by its absence, along with faster updates to the AirPod range.

Then there’s Tesla. Elon’s empire has many flaws — but delay tolerance isn’t one of them. The Model 3 launch was a mess: production hell, bottlenecks, delivery drama. But it shipped. And from that point on, Tesla owned the mental real estate of EV mass-market viability.

No one remembers the wait times. They remember the cars. Because products, once shipped, become real. And reality always beats roadmap. And if the guy inventing these amazing machines has a bit of a quirk and allegedly enjoys a quick bump of ketamine in the White House, well, considering what used to on under the Oval Office desk when Clinton was sitting their, and his spliff smoking where he “did not inhale,” well, what’s a bit of horse tranquilliser between friends

These weren’t miracles. They were just decisions. Decisions to act. To stake a claim. To get in the hands of users and start the messy, glorious process of becoming real.

This is where Apple has faltered. Not in ambition. Not in engineering. But in the guts to launch before the stars align.

And ironically, it’s where Steve Jobs excelled.

“It’s more fun to be a pirate than to join the navy.” — Steve Jobs

The pirate ships. The navy forms a committee. The pirate breaks something. The navy logs it in Jira. Jobs didn’t wait for market readiness. He provoked it. The iPod didn’t launch into a sea of demand — it created the demand by existing. The iPad wasn’t asked for. But it delivered. The Watch? Just as wearing a wristwatch had been written off as an anachronism, suddenly it was back, recreating the industry much as Swatch had done two decades earlier, but ingle handedly outselling the entire global watch production ingle-handedly in just a few years.

That’s the muscle Apple hasn’t flexed since Jobs left. The pirate spirit has been replaced by navy logistics. And logistics don’t make legends. They make… delays.

Act VII: What Apple Could Have Shipped (But Didn’t)

There’s a myth that Apple always gets there in the end.

But in this market, “eventually” is often indistinguishable from “never.”

Execution delays don’t just cost quarters. They cost categories.

And Apple, in its post-2015 naval-gazing mode, has developed a dangerous habit: treating missed opportunities as market validation that the idea wasn’t worth it in the first place.

Spoiler: but they were.

And some of these moments weren’t just missed. They were gift-wrapped to competitors.

“If you don’t cannibalise yourself, someone else will.” — Steve Jobs

Tim Cook’s Apple knows the quote. It just doesn’t believe it. And so the dithering began.

• The Low-End MacBook That Never Came

For over a decade, educators, students, and emerging markets begged for an affordable MacBook — the spiritual heir to the white polycarbonate MacBook that ruled campuses and coffee shops in the 2000s.

Apple, instead, offered the MacBook Air at $999, barely refreshed. Then it cancelled the Air. Then it brought it back. Then it raised the price. Then it introduced the M1 at $999 again.

Meanwhile, Chromebooks ate the education sector alive. Apple could’ve owned that market. But it blinked. Because “premium” became theology, not strategy.

• The HomePod Mini… Five Years Too Late

The original HomePod was an acoustic marvel with Siri duct-taped on. Launched at $349 in a market flooded with $49 Echo Dots and $29 Google Minis.

It flopped. Apple cancelled it.

Then, years later — in a move that felt suspiciously like learning — they launched the HomePod Mini at $99. It was great. People loved it. To add insult to injury, Apple released a barely changed HomePod 2, and made it incompatible for “Spatial Audio” with HomePod Gen1s which were by that time unavailable, condemning earlier buyers of these expensive speakers to either buy new HomePod 2s, ditch the system altogether for a Sonos system perhaps, or just pretend they didn’t care and just position their old HomePod in a centre position at the front of the room, and two new paid HomePod Minis at the rear of the room by the sofa, in paired mode, all three then paired together, to try and regain the effect (which works fairly well, but is not an “approved” use case).

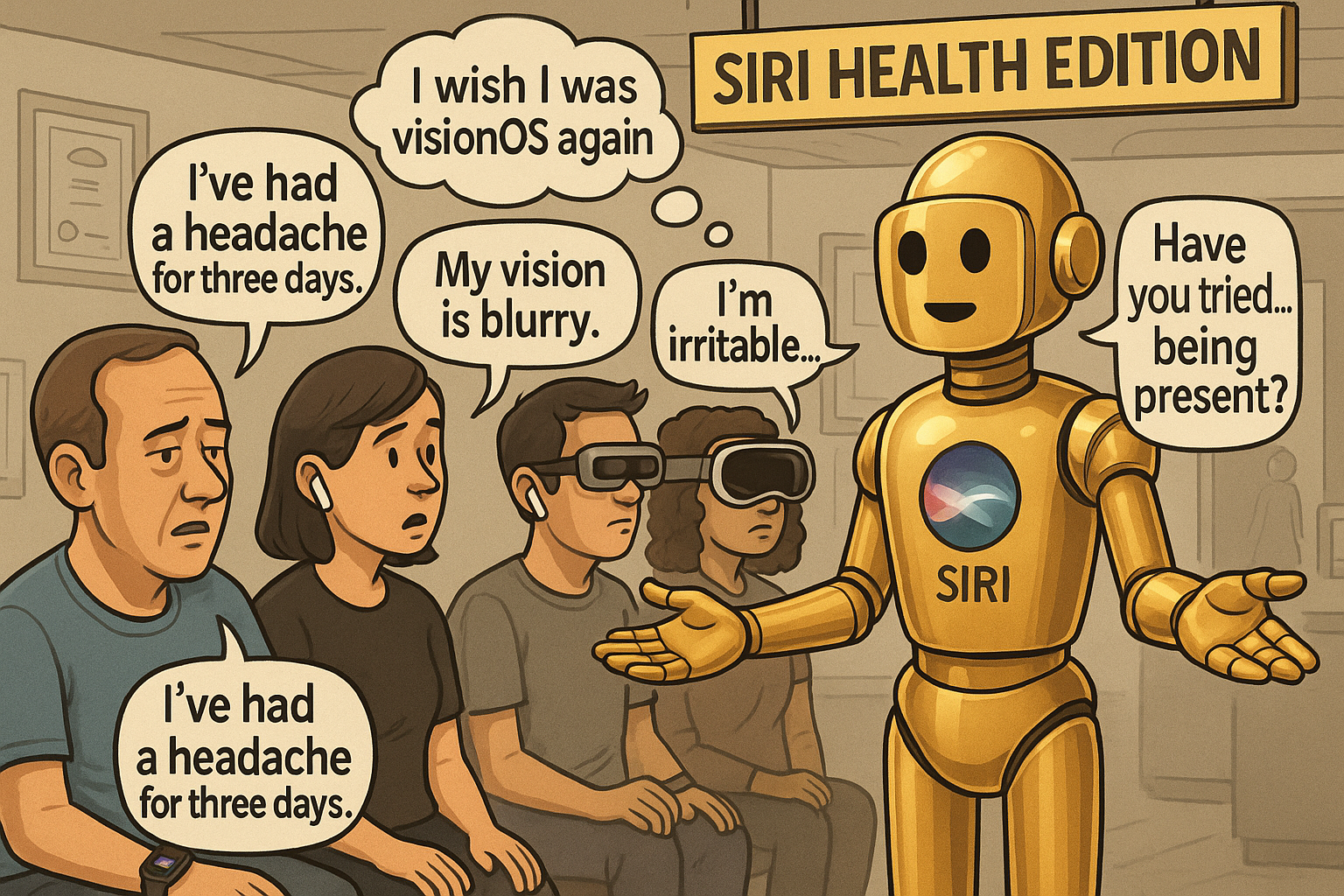

But by then? The smart home had moved on without them. Routines, presence detection, speaker groups — Apple was no longer the conductor. It was just a well-dressed flautist at the back of the orchestra having flogged off its old instruments to collectors and producing an iterative update now playing host to homeless versions of a dementia-ridden Siri that can’t really remember its purpose, but enough to play music, give a weather report, and tell you what the temperature is in the room next door. That’s progress for you!

• A Proper HomeKit Interface (Still MIA)

Imagine designing the world’s most privacy-conscious smart home protocol… and then making the app experience so hostile it feels like it was ported from a 2012 Samsung fridge. HomeKit’s UI has been a design crime for a decade. Cluttered tiles. Non-intuitive automation. Glacial syncing. It’s a case study in how software neglect can sabotage great hardware. Even Matter — the cross-platform saviour — hasn’t fixed this. Because Apple still acts like interface design is a one-time event, not a living conversation And Matter, for all its promise, just keeps on resetting itself (or perhaps HomeKit just deliberately loses the handshake) and you have to pair the device all over again. Pretty poor show

• An Apple TV That Wasn’t Afraid of Serious Gaming

Here’s the one that stings: the Apple TV has everything it needs to be a category disruptor. A tight OS. A gaming-capable chip. A living-room foothold. A payments system. A captive user base.

What it doesn’t have? A strategic will to own gaming, although they’ve trailed a change to this at WWDC (again, it will be down to execution).

Instead of making a compelling controller, offering game streaming, or incentivising devs with meaningful revenue shares, Apple turned the Apple TV into a weirdly expensive Netflix box.

The result? Xbox Game Pass and Nvidia GeForce Now won the war Apple never bothered to fight.

• Modular Accessories for iPads and iPhones

The iPad has tried to be a laptop for nearly ten years now. But modularity has always been one accessory too far.

A real keyboard system. A dock with expanded ports. A hardware touchpad interface before the Magic Keyboard arrived late. These weren’t moonshots — they were market-standard features Apple just… couldn’t be bothered with until competitor pressure forced their hand And now we have an almost-MacOS running on the iPad - 10 years late - courtesy of iPadOS26

This isn’t innovation. This is tactical reaction.

• A SiriOS SDK… in 2020

The original Siri team begged Apple to open up the voice layer. Instead, Apple wrapped it in NDAs, laggy APIs, and an identity crisis.

By the time ChatGPT exploded into public consciousness in 2022, Siri felt like a 2014 Toyota trying to race a Tesla Roadster.

Had Apple launched SiriOS in 2020 — a proper developer toolkit, agent-based logic, local runtime — it could have built an AI-first ecosystem before OpenAI had finished its first alignment workshop. It woudn’t have needed an LLM at that point, just ML agents, which together would have acted in much the same way as n my SenseOS concept.

Instead, the most valuable computing surface in the world — your voice — was effectively leased out to Alexa, Google, and now ChatGPT.

These weren’t wild bets. These were obvious plays. Missed not because they were flawed, but because Apple had grown so addicted to the idea of doing things “the Apple way” that it forgot how to do them at all.

The result? Entire categories ceded. User goodwill eroded. Developer trust frayed.

Not a hate crime. Just an observation.

“You can’t con people in this business. The products speak for themselves.” — Steve Jobs

They do. And the silence from these ghosts? Deafening.

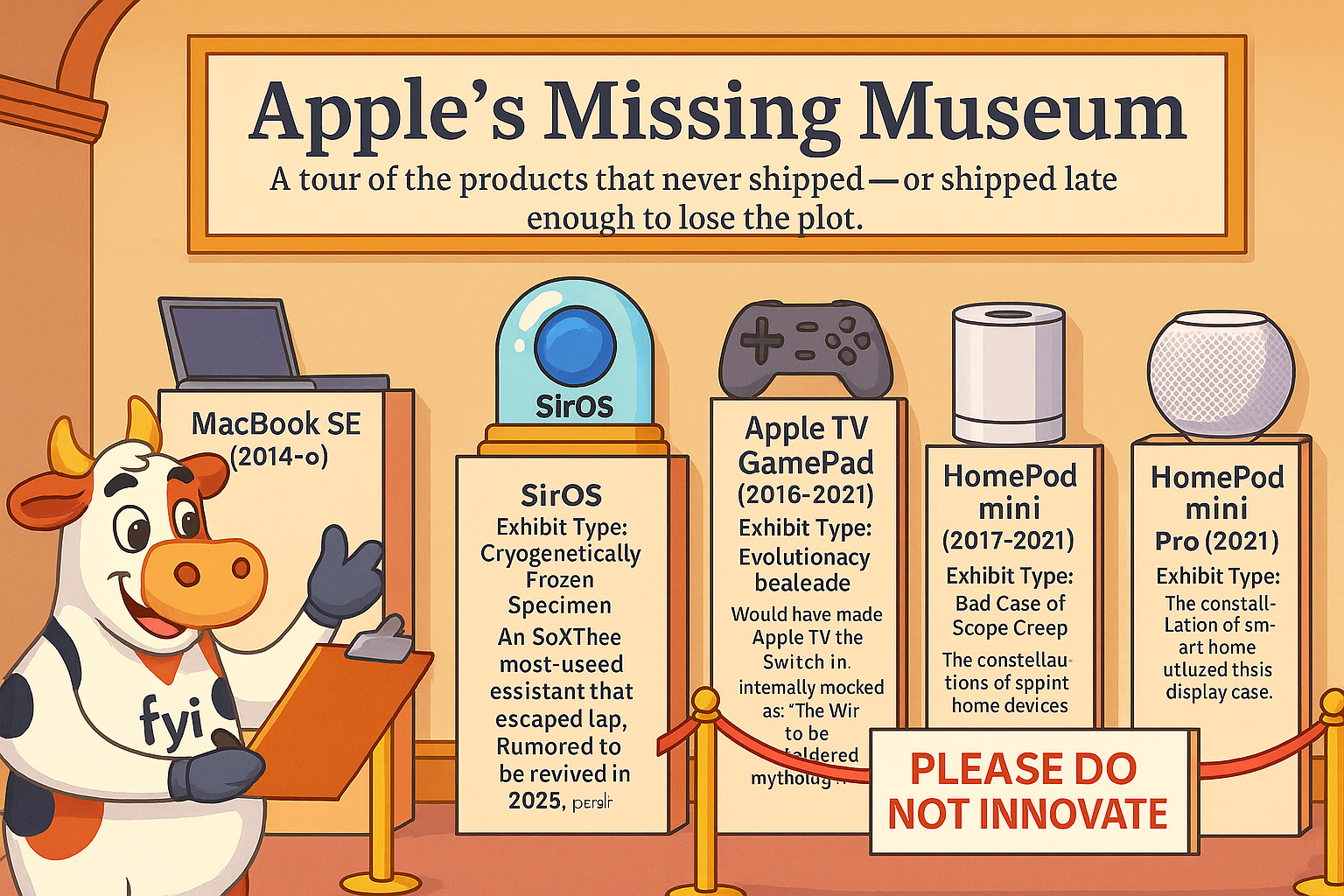

🏛️ Apple’s Missing Museum

A tour of a few products that never shipped — or shipped late enough to lose the plot. Please don’t touch the exhibits - they’re vapourware 3D projections.

🖥 The MacBook SE (2014–∞)

Exhibit Type: Phantom Fossil

An affordable MacBook for students. Lightweight, low-cost, unbranded ports. Killed during the Great Margin Purge of 2013.

🧠 SiriOS (2016–?)

Exhibit Type: Cryogenically Frozen Specimen

An SDK for the most-used assistant in the world. Never escaped the lab. Rumoured to be reviving in 2026, pending thaw cycle.

🎮 Apple TV GamePad (2016–DOA)

Exhibit Type: Evolutionary Dead End

Would’ve made Apple TV the Switch before the Switch. Internally mocked as “the WiiToo.” Now considered mythological.

📱 Modular Smart Case (2015–DOA)

Exhibit Type: Artefact in Jony’s Sketchbook

A case that added battery, storage, and camera bump. Jony called it “a wart.” Shipped instead as the world’s ugliest battery case.

🏠 HomeKit UI v1–v12 (2014–Stillborn)

Exhibit Type: Interactive Horror Installation

Touchscreen tiles from the uncanny valley. One button arms your alarm. The other microwaves your dog. Nobody knows which.

🔊 AirPower (2017–DOA)

Exhibit Type: Schrödinger’s Charger

Demoed live. Featured in ads. Cancelled due to heat issues. Still hotter than HomePod sales

🧠 Siri 2.0 (Missing In Action)

Exhibit Type: Living Fossil

Preserved in amber. Occasionally mutters something about web search. May one day evolve. May also be a parrot. We’re told it may appear in 2026. Sometime.

🏛 Museum generously funded by Services revenue and retail floor polish.

Act VIII: But Now… Something Has Shifted - post WWDC25

“We’re not going to be the first to this party, but we’re going to be the best.” — Tim Cook (on Apple’s AI posture, 2023). Actually it was a Steve Jobs quote, but I bet its one Tim Cook wished he’d quoted a couple of years ago.

For all the justified frustration, something about WWDC 2025 felt… different. Not in the usual keynote sparkle sense — Apple always delivers a good show. But in the subtext, in the timing, and in the unusually sharp edges of what was said and what wasn’t.

Gone were the hollow phrases like “magical” or “delightful” repeated ad nauseam by execs coasting on TelePrompters and paragliding into CGI version os of Apple’s Spaceship. In their place, we got specificity. Not full answers, not full confidence — but something resembling candour - and a remarkable lack of the announcement of anything ambitious. Apple’s sting from 2024s failure was still hurting. In fact the introduction to WWDC - a developers’ conference, was Craig Federeghi driving around the top of the Apple Campus being coached by Tim Cook to promote their new F1 movie epic starring Brad Pitt. Unless this movie heralds the start of F1 streaming to AVPs, heartland g a use case at last, and perhaps intersecting with an immersive F1 simulator, I’m unsure why it was used to take up valuable keynote time for a developers’ conference. Except Apple didn’t really have much of substance to announce publicly.

Instead of mystery, we got structure. Apple Intelligence, for once, had an architecture — not just a marketing pitch. There was a visible agent model. A clear SiriOS layer similar in concept to my SenseOS layer. A nod to local LLM processing and the neural engine. And, crucially, a date: Spring 2026. Not the best news. But finally — news with a timeline. It marked the first time since 2020 that Apple had laid out an ambitious product vision that was both conceptually mature and openly delayed — but without pretending it was something it wasn’t.

And that alone was a shift. Because Apple’s recent cultural pattern has been one of denial: over-promising, under-delivering, and gaslighting through omission:

Siri wasn’t bad — it was just misunderstood.

The AVP wasn’t flopping — it was “spatial computing.”

HomeKit didn’t fail — the industry just hadn’t caught up yet.

At WWDC 2025, Apple didn’t spin. They acknowledged. Quietly. Implicitly. But still. There was also — finally — a nuanced sense of humility.

Craig Federighi, usually the smirking showman, leaned into a more subdued tone. No skits, no flirty hair flips (apart from when he whipped off his F1 helmet). Just a cautious walkthrough of what Apple intends to do, how it might work, and what developers might get to touch — someday. In a space increasingly dominated by hype merchants and premature agents that “hallucinate responsibly,” Apple looked… sobered.

And that too is new. A company finally realising that it has spent more than half a decade overpolishing its glass and underdelivering its substance. That realisation matters. Because it was the same quiet internal reset that preceded Apple Silicon.

Remember: the M1 story didn’t start with a triumphant press release. It began with the embarrassing acknowledgement that Intel couldn’t keep up, that Apple’s laptop roadmap was stalling, and that it was time to own the stack again. From that admission came one of Apple’s best execution arcs in a decade.

Could WWDC 2025 mark the same kind of inflection?

Maybe. But here’s the catch: the last time Apple pulled that off, the entire roadmap was already built in secret. By the time the world knew about Apple Silicon, the M1 chip was already in test machines. The MacBook Air redesign was already done. The launch timeline was locked.

This time?

Everything’s in the open. Everything’s in flux. The roadmap is still aspirational. The AI stack is still a concept. SiriOS doesn’t exist in beta form. Developers haven’t touched a line of API. And we’re still not clear whether Apple intends to allow 3rd party LLMs to persist data, customise agents, or run autonomously across contexts Or in fact whether it will have context or intra it inter-session memory at all, the most important aspect of the current debate around LLMs.

That’s not a roadmap. That’s still a sketchbook. But sketches are better than silence. A sketchbook is still progress. So yes, something has shifted. It’s not yet culture. It’s not yet discipline. But it is tone, posture, and acknowledgement. In an industry full of bravado, maybe Apple is learning the hardest part of re-earning trust:

Stop pretending you’ve shipped. Admit you haven’t. Then prove you will.

Act IX: Tells to Watch (The Trust Timeline)

“You’ve baked a really lovely cake, but then you used dog shit for frosting.” — Steve Jobs (on MobileMe, 2008)

There’s a difference between cautious optimism and reckless belief.

And in the case of Apple’s AI roadmap, the difference is measured in tells. Signals. Indicators that what was announced on stage at WWDC 2025 wasn’t just frosting — it was the beginning of a real cake. Baked, built, and ready to serve. Because if we’re being honest, the frosting smells familiar.

We’ve been told before that Siri would evolve. That HomeKit would lead the smart home. That Apple’s products were “years ahead” of the competition — only to discover they were quietly being overtaken by faster-moving, scrappier rivals who shipped. This time, if Apple wants to avoid another AI “MobileMe Moment,” we need to see evidence.

Here are the five key execution tells that investors, developers, and anyone still paying attention to the arc of Apple’s AI strategy should be watching between now and WWDC 2026:

1.A Siri SDK Actually in the Wild

“Next year” isn’t a roadmap. It’s a delay with good lighting.

If Apple wants Siri to become an ambient, context-sensitive agent, it needs developers. It needs use cases. And it needs to stop pretending that it can bake all of that internally behind closed doors. The SDK for SiriOS must be real, public, and live in developer hands no later than Q1 2026.

If we don’t see this, it’s not happening in iOS 27. Period.

2.Siri Beta Testing in Public iOS Builds

Not carefully stage-managed demos. Not Apple Store-only trials. We mean actual SiriOS capabilities in the hands of users on public betas — including functional agent handoff, natural language flows across apps, and some version of Siri memory.

If Siri 2.0 is still behind glass in April 2026, then “Spring” is off the table. Again

3.Agent Integration Across Apple’s Core Apps

This is the proof of life.

If Siri is becoming the brain of Apple Intelligence, it must show up everywhere:

• In Calendar, helping coordinate not just appointments, but prep and commute time.

• In Mail, summarising threads and anticipating draft replies.

• In Messages, interpreting tone or suggesting context-aware nudges.

• In Reminders, inferring actions from conversation — and completing them.

If these integrations don’t appear in native apps — even in rudimentary form — the whole premise of agentic UX is still vapour.

4.UI Coherence Between SiriOS and VisionOS

Apple’s future hinges on coherence. If Vision Pro is the spatial manifestation of their next-gen computing model, and SiriOS is the conversational UI layer… they must speak the same design language.

If VisionOS evolves in one silo, and SiriOS in another, it’s Newton vs Mac all over again — incompatible verticals that confuse instead of converge.

Look for unified gestures, visual metaphors, and behavioural norms. If they align? We’re getting somewhere.

5.On-Device LLM Beyond Summarisation

A local LLM that only summarises notes or rewrites emails isn’t intelligence. It’s Grammarly with better branding.

For Apple Intelligence to be credible, we need to see:

• Multi-modal on-device inference

• Contextual awareness based on local device state

• Real task execution (e.g. “Prepare me for my meeting” = files, mail, time, contacts)

Apple’s Neural Engine is good enough. The question is whether Apple is brave enough to let it run.

Each of these five tells is objective. Not vibes. Not marketing. They’re execution milestones. And if we don’t see at least three of them clearly demonstrated by April 2026, we’ll know Apple has once again slipped from shipping to storytelling.

Because unlike in 2024, this time the market is watching. And trust has a half-life which is now being extremely stretched after being pushed off a cliff down to 2026, from 2024 originally which was already deemed as “rather late.”

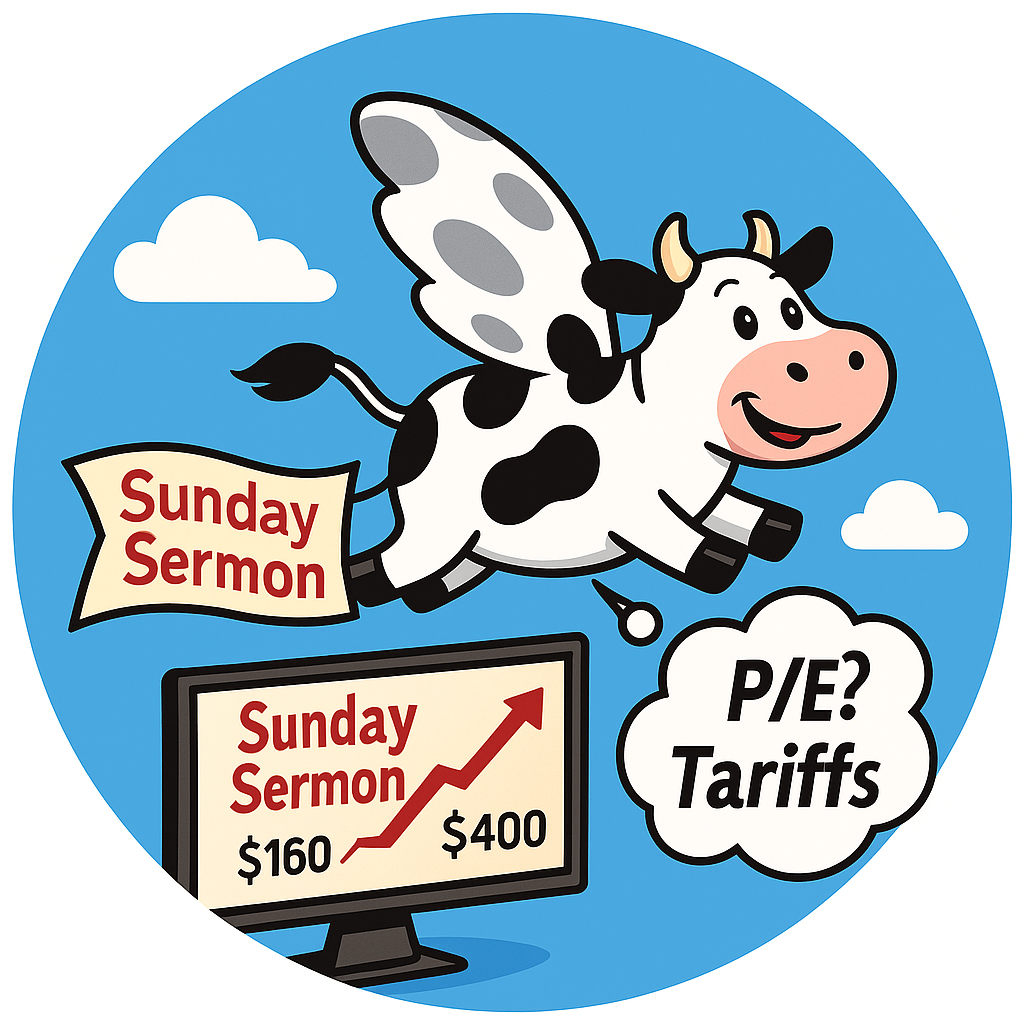

Act X: The Multiple Is Not Entitlement

In the theatre of tech, Apple is the master set designer. But behind the velvet curtains, Wall Street doesn’t watch the stagecraft. It watches the numbers.

And right now, Apple’s story is outpacing its math.

At the time of writing, AAPL trades around $197, down from a $260 peak and up from its $169 low a couple of months back. That’s not a disaster (unless you followed Dan Ive’s advice and price targets in March with a target of $325 and a tireless suggestion to just Buy Buy Buy all the way down to about $220 before exhausting himself)— but it is a quiet stagnation, especially compared to the broader S&P and tech peers riding the AI wave. The company has been buoyed not by earnings growth, but by the residual faith in its future, embedded in its 25x P/E multiple.

The problem? That multiple now has nothing to lean on.

It’s standing on a tightrope made of two strands:

• A 2026 promise of Apple Intelligence + Siri 2.0

• A 2026 hardware tie-in with iPhone 18

Neither exist yet.

Let’s walk through why 2025 might be Apple’s most precarious financial year in a decade, and how execution — not marketing — will determine whether we’re headed for $400 or $160.

The Downside Math: $160 Isn’t Drama — It’s Just Deductions

Let’s be clear: the biggest bear case for Apple isn’t existential. It’s actuarial.

Here’s how we get to $160:

- Earnings Flatline

• iPhone sales are already under scrutiny.

• The “Air” version of iPhone 17 will help margins but may not move units.

• Gross margins remain vulnerable to CapEx growth, R&D outlays for AI, and… - Tariffs

• If Trump wins in his affirmation of his tariff structure — markets will begin pricing in aggressive tariff risk by July.

• Apple is uniquely exposed here: its China-centric supply chain, brand premium pricing, and reliance on US sentiment make it a direct target.

• Tariffs mean costs go up, pricing power weakens, and margins shrink. - PE Multiple Compression

• Right now Apple trades at a premium that assumes resilience and growth.

• If earnings go sideways and no product ships in a way that resets the narrative?

• PE could slide to 18–20x, in line with other “mature” tech companies.

Let’s do rough math:

• ×18 = $130 (apocalyptic)

• ×22 = $154 (bearish but plausible)

• ×24 = $180 (base case with weak growth)

• ×25 = $200 (what we’re clinging to now)

That’s your Apple spread. And right now, there’s nothing in the next 12 months to pull EPS meaningfully upward unless something ships. Soon. Where that multiple is placed on the spread will depend on what happen to earnings growth, whether it flatlines, or whether it goes negative comparably for a few quarters.

The Upside Case: $400 Is Real — But Conditional

Let’s flip the page.

$400 by late 2026/early 2027 is achievable if — and only if — Apple threads the following needle:

- iPhone 18 Is an AI Showcase

• Siri 2.0 and Apple Intelligence are fully integrated.

• The device isn’t just faster; it’s functionally different because of the software.

• This is an iPhone 4S / Siri or iPhone 6 Plus / big-screen moment. - Siri SDK Unlocks a Developer Renaissance

• Developers start building truly useful Siri integrations by late 2025.

• AI apps drive iPhone utility the way the App Store did in 2008–2012.

• Apple recaptures relevance not by dominating LLMs, but by turning its OS into the world’s best AI scaffold. - Markets Trust Again

• Apple sticks to the calendar.

• It hits at least two major roadmap milestones on time.

• Analysts, previously defensive, begin to revise price targets upward — not out of hype, but from visible traction. - China + Tariffs Avoid Worst Case

• Apple diversifies assembly in India and Vietnam more visibly.

• A Trump presidency softens tariff stance or targets other sectors first.

• Consumer resilience outpaces inflation and interest rate pressure.

If all that happens?

Then yes — with earnings growth suppressed between 2025 and 2026, and a return to growth, modest to begin with and then snowballing if Apple execute again to perfection through 2027 showing that their new software and hardware stack has both disrupted new AI and hardware ecosystems and surpassed them in term of UX and usefulness the a return to double digit earnings growth and a multipl back back t0 35, $360–400 is not fantasy. It’s an upper-bound base case.

But only if Apple ships And executed to perfection on all fronts. And stops alarming investors by picking fights with regulators, the judiciary, and almost landing Apple senior executives in jail for lying to the court.

Sentiment Snapshot: What Investors Are Really Thinking

Let’s recall Jorgen’s post from the comment section here in last week’s dive into the $160-400 range, asking what signs would prove this isn’t just another roadmap tease. And Dan Scropos’ follow-up, unpacking the real-world implications of Siri’s delay, Gruber’s analysis, and the fragility of trust.

We answered them both — in detail — and here’s the meta-analysis:

• The bullish investor is hopeful — but watching closely.

• The cautious investor is frustrated — but not yet pulling the eject cord.

• The bearish investor is pointing to the chart — already down over 20% in an enormous divergence from the underlying market, with no earnings narrative to defend the valuation.

This isn’t tribal. This is structural. Apple must now justify its premium with either:

• Exceptional execution, or

• Exceptional storytelling + believable follow-through

It currently has neither.

Closing Insight

Execution isn’t just about product delivery. It’s about clarity.

Wall Street and Main Street alike are no longer impressed by “coming next year.” If there’s no iPhone growth, no AI product shipped, and no SiriOS traction by Q2 2026, the P/E story evaporates. And that means Apple risks returning to where it was in 2013:

Admired, but mispriced. Trusted, but not believed.

Act XI: The Calendar and the Cow

If this piece has done its job, it’s not just a lament — it’s a call. Not to return to the past, but to remember what built the present.

Apple didn’t become the world’s most valuable company because of keynote charisma or temple-of-glass stores. It became what it is because it had a calendar, and it respected it. Because it had a product pipeline, and it honoured it. Because — above all — it shipped.

Vision matters. But charisma fades. And in the cold, evaluative gaze of the market — whether that’s Wall Street analysts, jaded developers, or disenchanted Gen Z teens — what remains is what you ship, when you ship it, and whether anyone uses it twice. Gen-Z’s latest fad? Using a Blackberry. No seriously, it’s a real thing. Of course, they have to use an iPhone to post this on social media, but, well, I think the point is made. Where the present is seeming ever less exciting to younger generations, they are increasingly turning retro. Every 20-something now wants to feel what it’s like to be a “90’s kid.”

We’ve covered the Newton. The iPhone. The iPad. We’ve touched the Power Mac, the Shuffle, the Apple Watch. Each was more than a launch — it was a loop: a v1 that learned, a v2 that matured, a v3 that dominated. Apple became Apple not because it was perfect, but because it iterated in public, at speed, with enough humility to course-correct before the world moved on.

That’s the art of execution.

That’s what today’s Apple is in danger of forgetting.

A Word From the Cow

At tommo.fyi, we have a mascot: a white cow with black spots, black horns, and black hooves — occasionally flying, often watching, and always mildly amused. You’ve seen it floating over Cupertino, clipboard in hoof, warning signs behind it. It doesn’t speak. But it sees, everything; it even watches Craig Federeghi‘s use of hairspray to correlate his daily usage to nervous twitches. The cow sees patterns, everywhere. Nothing escapes its eye.

And what it sees is this:

Apple still has the best supply chain on the planet.

Apple still has brand loyalty that’s irrational in all the right ways.

Apple still has the cash, the talent, the distribution, and the opportunity.

Mark Gurman still writes daily for Bloomberg for some unknown sum for recycling rumours he heard while writing his subscriber Sunday Ablutions column for some reason. Sometimes the cow feeds him some tips:

Oh, that wasn’t meant to sneak in - obviously this is nothing personal, I mean I wish could charge $300 for recycling what I’d read on Apple forms the previous week, but for some reason he’s got a great gig with Bloomberg as the Oracle. Nothing personal Mark. Good going on you (CNBC I’m open to offers).

Anyway back to the point.. none of this matters unless something ships.

This isn’t a hate piece. It’s a hope piece.

It’s a reminder that execution is the new charisma.

The Calendar Never Lies

Tim Cook isn’t Steve Jobs. That’s not a criticism — it’s a category difference. Cook is an operational genius. But that genius now needs to be redirected.

Not into logistics.

Not into services.

Not into margin games or privacy slogans or spectacles.

But into a clear, paced, public commitment to product evolution And not “exceptional” excellence, but “accessible excellence,” which people who didn’t buy their AAPL shares in 2001 and have lived off the dividends from ever since, can actually afford.

Vision Pro? Either evolve it into something real or shelve it and move on.

Siri? Ship a version that makes people stop muting it in frustration When it starts talking at the most awkward moments.

Apple Intelligence? Turn it from a brand wrapper into an ambient capability people actually trust. Like my SenseOS concept. And start trailing that now in the SDKs, well before Q1, or it’ll be too late for the current timeline of May 2026 to make much impact next year, after the damage which could hit the stock over poor iPhone 17 sales is realised. That’s not a forecast, it’s a heads up to a plausible scenario given this is the biggest likely “gap year” I can remember, for reasons already described.

And iPhone? Make it the thing everyone wants again — not because of marketing, but because it does something no one else does, and it’s here now.

Benediction

In the end, execution isn’t glamorous. It’s not a standing ovation. It’s not a meme. It’s not a press cycle. Execution is the quiet courage to deliver what you promised, even when no one’s cheering. It’s the humility to launch, learn, and improve. It’s the thing that keeps customers loyal, developers building, and analysts upgrading.

That’s what Apple needs now. Not more vision. Not more charisma.

Just… shipping. As the cow flies quietly above the spaceship, clipboard in hoof, whispering some final thoughts to Tim Cook as he smokes a quick pipe of hopium and prays he won’t have to sack any more senior execs:

Remember Tim, nobody’s asking for perfection. Just for something to ship on time, without any hopium needed.